|  |  | |

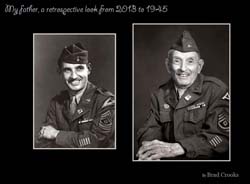

An up close and personal interview with U.S. Army Veteran and Togetherweserved.com Member:

1st Sgt Leonidas M Crooks U.S. Army (1942-1945)

This edition of "Voices" was written by 1st Sgt Crooks son Brad to honor and remember his Dad's service.

PLEASE DESCRIBE WHO OR WHAT INFLUENCED YOUR DECISION TO JOIN THE ARMY?

The morning after Pearl Harbor was bombed, my father and his friend went to the recruiting office in his small hometown of Parsons Kansas. They were turned away and were told it was the recruiters day off, and nothing was going to make him come in; war or no war.

Rather than waiting, my father and his friend drove 50 miles to Ft Scott, KS, where they enlisted into the service. My father's intention was to become a flying cadet in the Army Air Corps, but a fast talking recruiter saw that he had been to college, and had studied chemical engineering. My father was talked into the Chemical Warfare Service, thinking he would be in some sort of laboratory job.

Of course, the unit to which he was assigned was part of the Chemical Warfare Service and the 4.2 mortar he was to be introduced to was far from a laboratory. Mostly using high explosive, white phosphorus, tear gas and smoke, they were positioned throughout the war zone just behind the infantry. They were equipped with Phosgene, Mustard, and Chlorine gasses, should the war have escalated to Chemical warfare.

But a couple weeks later his ideas of flying were quashed as he boarded a Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad train bound for Ft Leavenworth, Kansas. Here, he was inducted and took the Military Oath. Soon after he and four others left the Kansas City Union Station on Jan. 2, 1942 for basic training at Edgewood Arsenal, MD. But a couple weeks later his ideas of flying were quashed as he boarded a Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad train bound for Ft Leavenworth, Kansas. Here, he was inducted and took the Military Oath. Soon after he and four others left the Kansas City Union Station on Jan. 2, 1942 for basic training at Edgewood Arsenal, MD.

His older brother, Dale, had enlisted the summer before Pearl Harbor, and was in the Army Air Corps. That, and a sense of patriotism and anger, were the forces that compelled my father to enlist.

WHETHER YOU WERE IN THE SERVICE FOR SEVERAL YEARS OR AS A CAREER, PLEASE DESCRIBE THE DIRECTION OR PATH YOU TOOK.

After completing basic training at Edgewood, the 2nd Chemical Mortar Battalion was moved to Ft Bragg where they completed Intensive Combat Training. During this time, they visited Camp Pickett for mountain exercises, as well as Camp Carrabelle, Florida to practice amphibious landings and scaling down rope ladders from ships.

My dad  returned to Edgewood Arsenal for NCO school, was promoted to corporal, and was selected to be the new B company clerk. He held that title until Salerno, at which time his First Sgt., George Bell, took a battlefield commission. returned to Edgewood Arsenal for NCO school, was promoted to corporal, and was selected to be the new B company clerk. He held that title until Salerno, at which time his First Sgt., George Bell, took a battlefield commission.

They could not promote him from corporal to First Sgt. so he was made Sgt. for a matter of days and then sewed on the stripes as First Sgt. of B Company. After only one and a half years in the U.S. Army, he was suddenly in charge of nearly 200 men and four platoons. He remained First Sergeant until his discharge on October 31, 1945.

At some point in Italy after his promotion, his former First Sgt. George Bell came up to him and said, "Crooks, whatever you do, don't let them make you become an officer." Lieutenants, of course, had to do Forward Observation, out in front of the infantry, calling in targets and directing fire.

The train that took B Company to Newport News, Hampton, VA pulled right up to a loading dock. The doors closed behind, and there was nowhere to go, but up the gangplank and onto the ship. The men didn't know where they were heading, Europe or the Pacific.

They boarded the USS Harry Lee; a banana freighter converted to a troop transport. The same ship would later transport the men on the invasion of Sicily. Days later they were passing through the Straits of Gibraltar headed to Oran, Algeria. They boarded the USS Harry Lee; a banana freighter converted to a troop transport. The same ship would later transport the men on the invasion of Sicily. Days later they were passing through the Straits of Gibraltar headed to Oran, Algeria.

It was a Sunday morning and very quiet when they passed through the narrow strait. Fear of becoming victims of a German U-Boats attack was on everyone's mind. My dad said he will never forget the passage the chaplain read...it was the Sheppard's Psalm..."And yea though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death......"

It was the largest trans-Atlantic naval convoy to ever cross the ocean. While passing through the straits, two ships were destroyed by the German U-Boats. Throughout the oceanic voyage, the ships changed course every thirty minutes in a crisscross pattern, to avoid detection.

IF YOU PARTICIPATED IN COMBAT, PEACEKEEPING OR HUMANITARIAN OPERATIONS, PLEASE DESCRIBE THOSE WHICH WERE THE MOST SIGNIFICANT TO YOU AND, IF LIFE-CHANGING, IN WHAT WAY.

The liberation of Prison of War camps always had a profound and lasting effect on my father.

During the advance on Germany, he participated in the liberation of a Stalag Luft, a POW camp for allied airmen located near Nuremberg and later, the final stage of the liberation of Dachau.

The  military prisoners at Stalag Luft were completely famished. "The officers and airmen were overjoyed to see us. They were just skin and bones; near starvation. There was a Chicken farm, nearby. I will never forget the looks on their faces, when we brought eggs to them," said my dad with a bit of emotion. military prisoners at Stalag Luft were completely famished. "The officers and airmen were overjoyed to see us. They were just skin and bones; near starvation. There was a Chicken farm, nearby. I will never forget the looks on their faces, when we brought eggs to them," said my dad with a bit of emotion.

But this did not prepare them for what lay ahead at Dachau. They had heard the rumors that a camp had been liberated by regiments of the 45th and 42nd Divisions, earlier that day. There is some ongoing argument as to who got there first, but suffice it to say, both were involved. Dachau was two things: A concentration camp, as well as a whole section that was dedicated as a school for the SS. Both divisions laying claim as first to enter, were probably correct, as the compound was huge, and entrances were made from different areas. My dad drove into Dachau with Lt. Holzworth and his best friend, Sgt. Marion "Andy" Andrew.

Here is the horror my father related during my interview: "We could smell it from the town of Dachau, which was probably a mile from the actual camp. We were used to smelling the dead and decomposition of animals and such, but this was different. When we reached the gates, we were simply appalled by what we saw. There were bodies piled everywhere, rail cars full of bodies. It was horrific. Bodies were stacked in large mounds, stripped naked with that terrible odor so pungent in the air. Here is the horror my father related during my interview: "We could smell it from the town of Dachau, which was probably a mile from the actual camp. We were used to smelling the dead and decomposition of animals and such, but this was different. When we reached the gates, we were simply appalled by what we saw. There were bodies piled everywhere, rail cars full of bodies. It was horrific. Bodies were stacked in large mounds, stripped naked with that terrible odor so pungent in the air.

"Every once in a while, you would see one of the bodies move, slightly. There were a few still alive, but just barely. We couldn't do anything for them, and even if we could, how can you justify helping one and not another; there were hundreds of them. Besides, they were so far gone.

"The infantry guys made the trustees pick up the decaying and dead bodies and put them on carts for burial. The trustees were hated by the prisoners more than the SS, I think.  Traitors to their own people. The 45th guys rounded up people in from the town and marched them through the camp, so there could be no deniability. They were all saying they had no idea, but that was a load of crap. There was no question what was going on out there. The smell was awful. Traitors to their own people. The 45th guys rounded up people in from the town and marched them through the camp, so there could be no deniability. They were all saying they had no idea, but that was a load of crap. There was no question what was going on out there. The smell was awful.

"I saw a private telling a local woman to drag a body over to a pile. The Army made the trustees and locals pick up the bodies and I suppose bury them. This old German lady stomped her foot and folded her arms and refused. The soldier chambered a bullet and pointed his Tommy at her, and her arrogance went away, and she did as she was told."

My dad's friend and counterpart, John "Durk" Durkovitz, 1st Sgt. of D Company, said he saw a prisoner come out of a compound, and through the gate. Walter Eldredge quotes John, in his book "Finding My Father's War": "He looked like a skeleton. His eyes were sunk way back in his head, and his skin was stretched tight over his bones. He saw me, and lit up with a big grin, and started towards me. About halfway, he stumbled. He was still smiling, but then he looked kind of blank and just folded up. I went over to where he was laying on the ground, and he was dead."

My dad carried four or five billfold sized pictures with him in his wallet for years after the war. People would comment that the holocaust never happened and my dad would say, "I was there" and pull out his photos. I used to wonder why those original pictures had gotten so crumbled on the edges. A few years ago, my father told me this to be the reason.

Eisenhower, he said, had issued a mandate that any GI with a camera, who entered these concentration camps, was to take as many photos as possible. He wanted it documented like nothing ever before.

Although "Durk" was able to give vivid, morbid details about what he saw at Dachau, my dad could not bring himself to talk too much about it, although he certainly shared more with me than to anyone else. I believe some of the reason was Dachau was a horrific, profound memory and some things one just can't talk about but for my father, I'm not so sure that was his entire reason. Although "Durk" was able to give vivid, morbid details about what he saw at Dachau, my dad could not bring himself to talk too much about it, although he certainly shared more with me than to anyone else. I believe some of the reason was Dachau was a horrific, profound memory and some things one just can't talk about but for my father, I'm not so sure that was his entire reason.

I think, early on especially, my dad felt it pointless to try to convey his experiences. A bond occurs with those who have seen combat, and have been exposed to the horrors of war. No film or book can ever really convey the emotion and experience of war. My dad once commented after seeing Saving Private Ryan, "It was a good movie, but no movie will ever capture what you feel. The smell...they will never be able to capture the smell."

Later in life, he enjoyed sharing his part in history, but for the most part, I think he felt it difficult to try to explain his feelings to those who were not there. They could not fully grasp what he was saying.

Though I was a non-combatant, when I joined the Air Force my dad seemed to open up, even more to me. When I took him to his first reunion, back in 1983, there were still a few of his actual wartime buddies attending. I just listened to conversations, and wrote down everything. When two men who served together, side by side, begin to speak, it is then one realizes just what an impact war has had on people.

I did asked him one time if Dachau was the worst thing he had to deal with during the course of WWII. He said no, that having to fight women and children had to be the hardest thing. He said that would eat at him. During the late months of the war, when entering and clearing towns, the Hitler Youth were so indoctrinated, that they would fight to the end, often as snipers. My father said if you ever looked a kid in the eye, you'd be dead, because they did not hesitate. I did asked him one time if Dachau was the worst thing he had to deal with during the course of WWII. He said no, that having to fight women and children had to be the hardest thing. He said that would eat at him. During the late months of the war, when entering and clearing towns, the Hitler Youth were so indoctrinated, that they would fight to the end, often as snipers. My father said if you ever looked a kid in the eye, you'd be dead, because they did not hesitate.

"One time near Frankfurt Am Main, we encountered some sniper fire from a house. We went to search the house and couldn't find anything. Finally I opened up a big trunk, and inside it was the 12 year old boy. He was Hitler Youth and didn't put up a fight. The Wehrmacht would desert these towns leaving women and young children behind to defend the cities," he reminisced.

I also think the starvation and the begging children in Italy got to him some. The soldiers were not supposed to, but they all shared their chocolate and rations with kids, who were never far away. Naples, he said was utter filth and poverty. Some of his pictures of these kids, really breaks one's heart.

"We would dig pits in the ground to put kitchen scraps and scraps from our mess kits. The Italian children and animals would come along and eat peelings and all these dirty scraps, from which they would become sick and diseased. The kids were just everywhere."

OF ALL YOUR DUTY STATIONS OR ASSIGNMENTS, WHICH ONE DO YOU HAVE FONDEST MEMORIES OF AND WHY? WHICH ONE WAS YOUR LEAST FAVORITE?

Favorite duty station would be Ft Bragg, without a doubt.

At the outset of the Civil War, his grandfather left Linconlton, N.C. to be conscripted into the Confederate Army in Ashville. Instead, he and his friend headed for the Cumberland Gap, where they hid out for 30 days, until they hooked up with the Union Army in Pennsylvania. Following the war, James Crooks never returned to NC, but relocated to Indiana;  leaving his brothers and family behind. leaving his brothers and family behind.

It was during my father's time at Bragg that he made the re-connection to the "Confederate" side of the family. During leave and holidays, he and his best friend Marion Andrew would head across the state to visit his distant cousin Mary, and her gal pals. A part of his own family that he and his own father never knew.

The cousins in NC gave him family, friendship, and a sense of stability, while he was preparing to go overseas during his military training. He met a girl, thanks to his cousin, and gained friendships that would last his lifetime. His Cousin, several times removed, would date his Army buddy Andy, and the two soldiers took many bus rides to the other side of the state, where they would go dancing (he was a master-jitter bugger), have a soda or go for a picnic.

The journeys to see the long lost family provided an escape from the rigors and stress of early life in the military, if only for a few days.

My dad cherished that time, and often lamented on how dear those memories were to him. I had the privilege to meet some of these folks, while travelling to and from 2nd Chemical reunions. He would comment, "They were so nice to me." Saying this with the utmost sincerity and gratitude.

Favorite overseas location was Austria. He loved the beauty of the country and the fresh air. The fact that the war had come to an end had to have made a big difference. He always said that if he were to go back, Austria is the one place he'd have liked to see once more. Favorite overseas location was Austria. He loved the beauty of the country and the fresh air. The fact that the war had come to an end had to have made a big difference. He always said that if he were to go back, Austria is the one place he'd have liked to see once more.

The winter of 1944-1945 was brutal, during the late part of Southern France through Ardennes Campaigns. It was the coldest/snowiest winter on record in the 20th century for that area and the men of the 2nd Chemical rarely came off the line, during this period of brutal weather. The war went on, regardless of Mother Nature.

My dad had a wool blanket and a hole cut into the ground for shelter, much of the time. I remember asking him about sleeping bags. He laughed and said, "Some of the officers had sleeping bags, we just had a blanket."

The snow was deep, the weather was frigid cold, and the artillery barrages were deadly. He told stories of the men's feet swelling up.  "If you took off your cold, wet boots, you'd never get them back on." Trench foot was a constant condition, as was severe frostbite. Compound this was setting up mortar positions. The 4.2 mortar barrel, (48 inches long, 105 lb.), the base plate (175 lb.) and the elevating standard (53 lb.) for a total weight of 333 pounds. They were constantly changing positions, so the Germans could not get a fix on them, as they were a priority target. "If you took off your cold, wet boots, you'd never get them back on." Trench foot was a constant condition, as was severe frostbite. Compound this was setting up mortar positions. The 4.2 mortar barrel, (48 inches long, 105 lb.), the base plate (175 lb.) and the elevating standard (53 lb.) for a total weight of 333 pounds. They were constantly changing positions, so the Germans could not get a fix on them, as they were a priority target.

He recalled that after having C-Rations for weeks on end, Thanksgiving of 1944 rolled around. Someone had managed to get a Thanksgiving meal set up for the men. As it was being prepared, however, a French general (The 2nd was attached to the First French Army at the time), came up with a priority target. B Company had to move out immediately, to a forward position to support the infantry.

By the time they got to the gun position and set up, the Thanksgiving meal they had hastily packed up had frozen in the time it took to move out and set up the gun position.  "The cranberry sauce had frozen solid and the turkey had ice crystals in it," he recalled. "The cranberry sauce had frozen solid and the turkey had ice crystals in it," he recalled.

I never asked my father what his least favorite assignment was, but that had to be high on the list. The Winter Line campaign in Italy had to be high on the list as well. Every mountain, river and every valley had to be fought for; in the middle of it was the famous Appian Highway or Highway 6; overlooking what was Monte Cassino. Rugged terrain, numerous casualty rates and filthy conditions, made this another least favorite location.

Tragedy stuck when two of my dad's men, holding a 4.2 mortar barrel, after a mortar round exploded inside the barrel, killing two men, and injuring several. To add insult to injury, the 4.2 shell came from a lot which had been manufactured at the Kansas Ordinance Plant (later Kansas Army Ammunition Plant) in my father's hometown of Parsons, KS.

FROM YOUR ENTIRE SERVICE, INCLUDING COMBAT, DESCRIBE THE PERSONAL MEMORIES WHICH HAVE IMPACTED YOU MOST?

Leaving the port at Hampton Roads, Newport News, Virginia, at twenty-three hundred hours, was a moment of complete silence for the men, each lost in their own thoughts and prayers, as the United States disappeared across the horizon of the Atlantic Ocean.

It was then, that my dad realized he may not see his home again. Yet the reason he was leaving was a noble cause, indeed. He never second guessed his decision to join the U.S.  Army nor the call to action. This was the norm for the Greatest Generation. He felt it to be a sense of duty. Army nor the call to action. This was the norm for the Greatest Generation. He felt it to be a sense of duty.

Photo is him sitting in a jeep as then entered Rome.

Upon his return, nearly 2 1/2 year later, my dad told his father: "I wouldn't do it again for a million dollars, but I wouldn't take a million dollars for the experience I have had."

He felt it was honor above self. He instilled this honor into me, a sense of duty that only comes from a great allegiance to a great constitution, nation, and flag. My dad's unspoken sense of patriotism was what compelled my own military service, which is a mere blip on the screen compared to his sacrifice.

He saw poverty and hunger of the children of Italy, the piles of dead at Dachau, and mankind at its worst. From this, his appreciation of this nation, and what he had fought for, were all the more substantiated.

My dad was a selfless individual. Always thinking of, and doing for others. It was the fabric of his generation. The war, perhaps, did not make him this way, but it certainly supported his personal values. It was a cause, after all, that he was prepared to die for.

Many of his battalion did just that.

IF YOU RECEIVED ANY MEDALS FOR VALOR OR AWARDS FOR SIGNIFICANT ACHIEVEMENT, PLEASE DESCRIBE HOW THESE WERE EARNED.

This excerpt is taken from the manuscript of my dad's WWII history. I have been compiling this since my childhood, and it was even a college term paper at one point. One day I will get all my notes together and finish a complete history. Here is story which led  to my dad's bronze star in 2011: to my dad's bronze star in 2011:

In the Casino Valley, events transpired that called for quick action, above and beyond the call of duty. I remember him once saying, "We just did it. We didn't think about it really, it was something that needed to be done and we did it. That's all; we simply reacted to the situation."

The first of the three Battles of Cassino ended on February 12, 1944. Soon after, elements of the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force were moving along a road, near San Michele. Their gear had been loaded on a mule train and the troops were on the move during a lull between the battles. The break in the fighting had provided an opportunity for the Allies to relieve and replace the battle-weary troops.

My dad and T/5 Herb Aram were asked by B Company CO Captain Paul Curran to go to the rear echelon, to pick up five replacements, and bring back PFC's Norman Gearhart and James Egoff, who were at the rear echelon.

It was on the return trip, that the Germans seized the opportunity to strike the New Zealand forces with their 88mm guns; unable to pass up at a the chance of a slow moving target. Aram pulled into a ditch, which my dad described as more of a narrow swag, than a ditch. It ran alongside the road, and allowed them to, hopefully, avoid becoming a target. Casualties began to mount quickly, as mules were being hit, thus blocking the road

Aram and dad watched from the low area, as the shelling continued to bombard the NZ troops injuring and killing many. "A lot of those men are going to die out there today, unless we do something", he told Aram. "Sergeant, I'll drive if you load them up," Aram replied.

My dad ordered his men to stay where they were and to stay down. He and Aram made for their vehicle (a weapons carrier) and prepared to go out onto the field under fire to help the wounded soldiers. My dad ordered his men to stay where they were and to stay down. He and Aram made for their vehicle (a weapons carrier) and prepared to go out onto the field under fire to help the wounded soldiers.

The road was too narrow to turn the 3/4 ton truck around. So Aram backed up 300 yards, moving slowly to avoid the dead and wounded soldiers, as the intense shelling continued.

"Aram did a helluva job driving. We would pull up, I'd get out and load the guys up, and we'd would move on to the next guy, and load him up. As soon as we got all we could handle, we'd drive back to the aide station, which was not too far behind us. We made three trips out there, under heavy German barrage. I remember the mules screaming with pain after being hit. It was terrible and awful sound. I will never forget that. It's funny, but that awful sound rattled me more than the men getting it. The soldiers were just sitting ducks out there for the Germans. After leaving the aide station the third time, we went back to get our men. That is when Aram told me, 'Sergeant, I think I have been hit.' He had been hit in the left bicep by shrapnel, and judging from the entry, it had to have come in on my side. Must have just missed me, because it entered the inside of his arm and went out the other. He didn't even know he had been hit, until that moment, after it was all over. Adrenaline, I suppose

"Anyway, I put Herb in for a DSC and a Purple Heart, but he was later awarded a Bronze Star, instead and the Purple Heart.

"When we got back, we couldn't find the men anywhere, they were not in the ditch where we left them. We hunted and hunted for them. Finally, we found them hiding in a haystack, of all things.

"There was this one kid, named Peachy scared to death --everyone was, of course, but he was panicked and I could tell he was getting ready to run. He wouldn't have made it ten yards, before he'd have gotten himself killed. So I just belted him one, to knock some sense into him, and to try to keep him down. Later, when we got back to the gun position, Peachy was telling some of the men what a great guy I was. One guy asked him what he had meant by that, and he told them, 'That first sergeant talked to me just like a father.' His platoon sergeant or someone told me about that," Dad chuckled. "I'll never forget that. He was just scared, that's all." "There was this one kid, named Peachy scared to death --everyone was, of course, but he was panicked and I could tell he was getting ready to run. He wouldn't have made it ten yards, before he'd have gotten himself killed. So I just belted him one, to knock some sense into him, and to try to keep him down. Later, when we got back to the gun position, Peachy was telling some of the men what a great guy I was. One guy asked him what he had meant by that, and he told them, 'That first sergeant talked to me just like a father.' His platoon sergeant or someone told me about that," Dad chuckled. "I'll never forget that. He was just scared, that's all."

He then told me about running into Captain Curran in New York after the war: "He asked me if I ever got my Distinguished Service Cross. I had no idea what he was talking about, of course. He said that he had put me in for it there at Cassino. I never knew anything about it, or even heard that I had even been recommended, for that matter. We figured the records were lost when headquarters was shelled by the Germans, during the Battle of Casino, or that it may have simply been overlooked, and lost in the 1972 fire at the St. Louis National Archives."

When I asked why he never pursued it, he said that at the time, he didn't care anything about it. He was just glad to get home. Later he told me his lieutenant in Italy, George Young, " would have gotten me my medal, but it's not that big a deal, really"

He received a Bronze Star in 2011, at age 91, thanks to efforts of then current 2nd Chemical Bn commander hearing about and researching this event. Thanks to Lt. Col Chris Cox, Maj. Don Twiss and Command Sergeant Major Kenneth Kraus for bestowing this honor to my father. My dad had never pursued this, but when I told CSM Kraus the story, at a 2nd Chemical reunion, the ball started rolling, and research was done. I understand Lt Col. Cox told his men, "We need to get this man his medal." My father had no idea this was being pursued. He received a Bronze Star in 2011, at age 91, thanks to efforts of then current 2nd Chemical Bn commander hearing about and researching this event. Thanks to Lt. Col Chris Cox, Maj. Don Twiss and Command Sergeant Major Kenneth Kraus for bestowing this honor to my father. My dad had never pursued this, but when I told CSM Kraus the story, at a 2nd Chemical reunion, the ball started rolling, and research was done. I understand Lt Col. Cox told his men, "We need to get this man his medal." My father had no idea this was being pursued.

Although the BSM citation my father received was officially given for "his service and outstanding combat leadership, from the line" throughout WWII, it was the aforementioned event that inspired the award. Lt. Col. Cox apologized to me, saying he wished he could have gotten him a Silver Star. There was need for apologies. After 67 years, my father was quite humbled. My father lay in a hospital bed, recovering from aneurysm surgery, when I broke the news to him that he was to receive the Bronze Star. One of three times in my life, I saw tears in my dad's eyes.

Because of the actions of my father and Herbert Aram, nearly 40 wounded New Zealand troops were rescued and certainly several lives were saved. My dad never talked about it much, save for the time I wrote a paper on him in high school and college. During his twilight years he began to open up some, but then only to few people or select groups. I am proud they acted so selflessly and bravely in service to their allied comrades. Because of the actions of my father and Herbert Aram, nearly 40 wounded New Zealand troops were rescued and certainly several lives were saved. My dad never talked about it much, save for the time I wrote a paper on him in high school and college. During his twilight years he began to open up some, but then only to few people or select groups. I am proud they acted so selflessly and bravely in service to their allied comrades.

Several years on a trip to Italy, my father visit the American cemetery in Anzio to pay respect to one of his men. My sister took several photos of him standing by the grave site of his man. When the curator told my father 3000 men were never recovered in Italy, he said he broke down and cried.

OF ALL THE MEDALS, AWARDS, QUALIFICATION BADGES OR DEVICE YOU RECEIVED, PLEASE DESCRIBE THE ONE(S) MOST MEANINGFUL TO YOU AND WHY?

Well the Bronze Star, was certainly special to him. Being recognized for something he had done nearly 70 years prior really touched his heart in a way I could not have imagined. He never expected such a thing. Well the Bronze Star, was certainly special to him. Being recognized for something he had done nearly 70 years prior really touched his heart in a way I could not have imagined. He never expected such a thing.

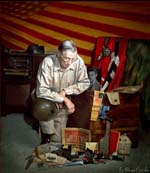

It isn't a medal or device that was most meaningful, however. The thing my dad was very attached to was his invasion flag. The canvas armband with the American Flag, which was worn by amphibious assault troops and by the airborne forces.

That flag, when he held it, would bring back memories. I never pressed him much for stories he didn't want to tell, but that flag had seen some terrible things and I know he wore it with pride. The photo is his flag along with his canteen

WHICH INDIVIDUAL(S) FROM YOUR TIME IN THE MILITARY STAND OUT AS HAVING THE MOST POSITIVE IMPACT ON YOU AND WHY?

My father was a deeply religious man. In a V-mail letter to his father, he wrote about his chaplain. He mentioned that a lot of the guys would laugh at the chaplain and make fun of him. But my dad said that he felt the one man who was doing as much if not more than anyone in combat, was the chaplain.

One of my dad's favorite officers was a man named 2nd Lieutenant George Haywood Young, Jr. Dad was actually slightly more than one year older than Young, but Young proved himself to be an excellent and bright officer. He was solid in combat, and one always knew where he stood. He demanded discipline and got it.

My father was always impressed with him, and the stories I have of Young are quite remarkable and some very funny. Young knew he was inexperienced in the field when he came to my dad's Company from D company, following Sicily, he always valued the opinion of his First sergeant, whether it was Bell or my father. He had a great respect for his NCOs. A trait that followed him his whole career, through Vietnam. After the Italian invasion Young was fast-tracked to 1st Lt, and soon after, made Captain. My father was always impressed with him, and the stories I have of Young are quite remarkable and some very funny. Young knew he was inexperienced in the field when he came to my dad's Company from D company, following Sicily, he always valued the opinion of his First sergeant, whether it was Bell or my father. He had a great respect for his NCOs. A trait that followed him his whole career, through Vietnam. After the Italian invasion Young was fast-tracked to 1st Lt, and soon after, made Captain.

My dad said he always knew George Young would go far in the military. And that he did. He retired as a Brig. General, and was one of the most decorated officers of the 20th century.

Before he passed away of congestive heart failure, I had the honor to meet Brig Gen Young, at Ft Leavenworth, KS, in 1995. My dad and I made the trip up there from Kansas City where I live to see him. I felt like I was meeting an icon, my dad had built him up to me so much, for so many years.

My father blushed when the general told me, "Brad, when I came into the unit, I was green and had no idea what I was doing. It was your dad who taught me what it was, to be a soldier." The respect went both ways. My dad never served for such a fair and honest officer, as Young.

As we were leaving the golf pro shop/clubhouse on post, Young asked me a question. "Did your dad ever tell you we were in the FBI?" I'm sure I shot him a confused look. He laughed and said, "Yeah, we were the Forgotten Bastards in Italy!" This was in reference of course of Italy being the forgotten campaign, despite losing nearly 400,000 allied troops there. If you listen to many historians, June 6, 1944 was the only battle fought in Europe. As we were leaving the golf pro shop/clubhouse on post, Young asked me a question. "Did your dad ever tell you we were in the FBI?" I'm sure I shot him a confused look. He laughed and said, "Yeah, we were the Forgotten Bastards in Italy!" This was in reference of course of Italy being the forgotten campaign, despite losing nearly 400,000 allied troops there. If you listen to many historians, June 6, 1944 was the only battle fought in Europe.

General Young is interred at Arlington. You can go to my profile page and you will find a link to the Remembrance Page that I made for Brig Gen Young, if you'd care to read more.

Being a first sergeant my dad spent quite a lot of time with officers which he considered himself fortunate, as most of the officers, with a couple exceptions were the cream of the crop. From the stories I have been told, most set a fine example for the men of 2nd Chemical.

At Ft. Bragg, one of the young 2nd Lieutenants, a fine officer named Frank Martin, was exiting a building with of his hands completely full of papers and books. My dad was approaching the building as Martin exited. With proper military protocol, he rendered a sharp salute. Lt. Martin instinctively fumbled to raise his own arm in a return salute; in the process dropping the entire load he was carrying, onto the ground. The young Lt. with thick eyeglasses simply chuckled, and said, "You Son-of-a Bitch!" Dad always maintained proper military bearing, even when an officer had his hands full.

My dad's favorite General, who he had the opportunity to meet once, was General Patton. He said Patton saved more men by not over thinking and by just doing his job. According to my dad, anyone who says  "His guts and everyone else's blood" never served under him. Those who served under Patton loved him. Even the young private he slapped, and was ridiculed for, later said it was the best thing that ever happened to him. "His guts and everyone else's blood" never served under him. Those who served under Patton loved him. Even the young private he slapped, and was ridiculed for, later said it was the best thing that ever happened to him.

And General Bradley, for whom I was named, was another. My dad had a great respect for Omar Bradley. He was decisive, and a soldiers general, according to my father. He also was often the mediator between Patton and Eisenhower.

My dad lived his life as a hard worker and a generous man. From his deathbed in April of 2014, he was writing get well cards to others in his church, as well as birthday cards and any other type of greeting to help lift someone's spirits. He was selfless and always looking out for others. Often, in the military, the captain would have my dad write the letters to the parents, regarding fallen soldiers. I think it was this compassion that carried through to him until his final days.

He never understood why he lived through the war, while so many others around him died. He felt he owed it to the memory of the fallen, to live his life in an honorable way, and that he certainly did. He never understood why he lived through the war, while so many others around him died. He felt he owed it to the memory of the fallen, to live his life in an honorable way, and that he certainly did.

As for politics of the time, he loved "Give 'em Hell, Harry" Truman. He always felt Truman made the right decision to drop the bomb. He had orders to fly out and prepare to go to the Pacific when the bomb was dropped.

He credits Truman for saving thousands of American lives by doing so.

CAN YOU RECOUNT A PARTICULAR INCIDENT FROM YOUR SERVICE WHICH MAY OR MAY NOT HAVE BEEN FUNNY AT THE TIME, BUT STILL MAKES YOU LAUGH?

Near Nice, France, when the men weren't standing watch on ready guns, they often explored the hills of Southern France, looking for the friendly companionship of local girls, and the comforts of small villages.

"We got acquainted with some of the local girls. I had picked up some French and had  gotten pretty good at speaking the language," My father recalled. "We would arrange to meet them up in the hills, above their villages. We would come down, and they would come up. Often the Germans would occupy a town by night and we would occupy it by day. There was no front line really. As you moved east, you were more likely to run into German patrols, and as you moved west, you were more likely to run into our patrols, than theirs. gotten pretty good at speaking the language," My father recalled. "We would arrange to meet them up in the hills, above their villages. We would come down, and they would come up. Often the Germans would occupy a town by night and we would occupy it by day. There was no front line really. As you moved east, you were more likely to run into German patrols, and as you moved west, you were more likely to run into our patrols, than theirs.

"I remember one day we met these girls and they told us that they had seen a Kraut patrol that was going to pass along the trail on the ridge below us. So we gathered a bunch of big rocks and waited. When the Germans were just below us, we started rolling these big rocks over the edge and right into the middle of them.

"It was funny to be rolling rocks onto a combat patrol, but just up the hill we were safe. By the time they finished dodging all the rocks and came up the hill looking for us, we were long gone. We found a nice place further up the hill and had a picnic with some of the rations we brought along."

Another time, while in Germany, one of the mortar platoons had not shown up, and were long overdue. There had been no communication with them. Finally, the Captain asked dad to go look for them. He and Driver T/5 Herbert Aram got in the company jeep and went off to find the missing men.

"Aram and I just took off in the jeep, and headed for the last known position where the missing platoon was supposed to have been. We were unable to locate them, after some time, and we were pretty much in no man's land, so we decided to head back."

"This combat engineer lieutenant came running down toward us, flagging us down, and asked us what the hell we thought we were doing. I told him we had been out looking for one of our mortar platoons that had not returned, and that we had just cut across a field. The lieutenant said, ' That Field over there?' I said yes we came from that direction. 'Sergeant, That field has been mined for over an hour!' We had just driven over a live minefield in a jeep. That Field over there?' I said yes we came from that direction. 'Sergeant, That field has been mined for over an hour!' We had just driven over a live minefield in a jeep.

"By the time we got back to the company, the missing platoon had already returned."

Another close call came in France or Germany, when he and his lieutenant went out in a jeep to scout out possible gun positions. They came upon tank tracks and began to follow them, thinking them to be those of Patton's 3rd Army. They drove into a town and noticed all the people were giving them strange looks.

My father said, "We stopped and asked some civilians 'where are the Americans?' 'Americans? There have never been any Americans here."

"We asked them, 'What about these tank tracks?' 'There are Tiger Tanks on the next street over,' they said, completely shocked at seeing the two of us there in an American Jeep."

I heard this story for the first time back when I was doing a paper on him in junior high school. I asked him, "What did you do?"

"We got the hell out of there, is what we did!" He exclaimed.

In searching for possible gun positions, they had inadvertently crossed over into German territory. My father said the outcome could have been much worse, had luck not been on their side.

WHAT PROFESSION DID YOU FOLLOW AFTER YOUR MILITARY SERVICE AND WHAT ARE YOU DOING NOW? IF YOU ARE CURRENTLY SERVING, WHAT IS YOUR PRESENT OCCUPATIONAL SPECIALTY?

Professional Photography. My father owned and operated a photography studio and camera shop in his hometown of Parsons, Kansas for 43 years. I shot this portrait of him in 1992. It was for his retirement, at the age of 72 from a profession he so loved. Professional Photography. My father owned and operated a photography studio and camera shop in his hometown of Parsons, Kansas for 43 years. I shot this portrait of him in 1992. It was for his retirement, at the age of 72 from a profession he so loved.

His interest in photography began early on in his military career. In Basic Training and during the course of extensive military training, he recorded many of his of leisure, with friends and companions.

Many times my father told me that, no doubt, it was World War II that peaked his interest in a photographic career. Now that he is gone, and even before, his snapshots are historically priceless to me, as a visual history of his military experiences and his life. What my dad was unable to express in words to me, he expressed through his photography. Sometimes, it was evident; as with his photos of Dachau. Other times it was not. A simple photo of Private Alfred Moore, taken in Italy, would later serve to help me to put a name with a face of a soldier, killed in action, while standing just a few feet away from my dad. His photos are my link to his memories and his story.

It was in Sicily and Italy that my dad began to pick up cameras that he would find along the way.  When not on the line, and occupied with the duties of a first sergeant, he took photos of his men, of places he had seen, and the occasional stray dog, lost due to the ravages of war. Occasionally he snapped a shot or two during battle, but rarely. When not on the line, and occupied with the duties of a first sergeant, he took photos of his men, of places he had seen, and the occasional stray dog, lost due to the ravages of war. Occasionally he snapped a shot or two during battle, but rarely.

He gathered some darkroom chemicals, and kept them in pickle jars and whiskey bottles, stored safely in his desk (which was a fancy, big wooden trunk, really). When he got a moment free, he would process the film in his pup tent by agitating it in pickle jars, and washing it in creeks and river beds. Soon, word got out that he Crooks could develop your film. It wasn't long before he was developing film for several of the men and most of the officers. It made him quite popular with the fellows, so he told me.

Often, he would just roll up the film, and wait until they found a town, where he could commandeer a photography studio, or find a willing photographer to print up his images.

Many of his negatives were never printed, until I found rolls and rolls of film. It was a treat to see some of the images my dad had taken, 60 years earlier, appear before my eyes, for the very first time.

As I have stated, my dad had some very fine officers. But there was this one 2nd Lt, (who I have many stories about), that was a replacement. He was fresh out of ROTC, and came into a unit of "seasoned" veterans. Lt. Applebaum was cocky. He was arrogant. And he thought he was God's gift to the Army. I have talked to no veteran who had much of anything nice to say about the man. Even after being with the unit for some time, he never changed.

My dad always chuckled when he told this story, or any story about Lt Applebaum, for that matter. He even said he kind of felt sorry for him....but not too sorry. This is how my dad tells of one incident: My dad always chuckled when he told this story, or any story about Lt Applebaum, for that matter. He even said he kind of felt sorry for him....but not too sorry. This is how my dad tells of one incident:

"We were in Frankfurt, I think. I found this photo studio; the one where I had that portrait taken in full battle dress. I had taken some of my negatives in there, and had been using this old German's darkroom to print up some pictures. Captain Young, Andy and several of the guys had given me their film to make pictures for them, so I got busy, while there was a break in the action.

"I had to leave for one reason or another, and when I returned, there was this sign on the door of the studio that read 'OFF LIMITS! BY ORDER OF LT APPLEBAUM'

"I walked over to the command post, we had established. Captain Young saw me come in, and asked me if I had his pictures for him. I said, 'No sir, I can't get in to print them. Lt Applebaum has it posted as off limits.' George shouted out "APPLE!'

"Apple came running over, got at attention and saluted, 'Yes Sir?'

"Captain Young shouted, 'Lieutenant! You have but one job in this man's Army, and that job is to do whatever the hell I tell you to do! Now you go down to that photography studio and take that God damned sign down!' None of us ever had any problem with Applebaum, after that."

That was always one of my dad's favorite stories to tell. I can guarantee I have heard it a thousand times. When I met General Young, back in 1995, he chuckled when I asked him about it, shook his head, and said, "Applebaum."

My dad had a great love for beautiful portrait work, and even as a soldier, he enjoyed browsing in the many portrait studios he would come across. In Nice, France, an old photographer invited him and Sgt. Andrew to sit and have portraits made. Dad said, "That old Frenchman was one of the finest photographers I have ever seen." The photo that Erpe' Studio in Nice made for my father was my dad's favorite picture. My dad had a great love for beautiful portrait work, and even as a soldier, he enjoyed browsing in the many portrait studios he would come across. In Nice, France, an old photographer invited him and Sgt. Andrew to sit and have portraits made. Dad said, "That old Frenchman was one of the finest photographers I have ever seen." The photo that Erpe' Studio in Nice made for my father was my dad's favorite picture.

One other time, after the Second Chemical had broken up, dad was on occupation duty with the anti-tank company of the 409th Infantry Regiment. He and his Lt, a man named Vale, were talking, and in comes this other Lt. On the shelf were several whiskey bottles, which were full of darkroom chemicals.

Lt Vale and my dad were talking and not paying much attention to the other officer, when the officer takes one of the bottles off the shelf, looks at it and pulls out the cork. Before my dad could say a word, the lieutenant took a big swig of photographic developer. Moral of the story, don't drink another man's whiskey, without his permission.

Long story, but that is basically how my father began his endeavor to become a photographer. He ended up with a very distinguished career, and was awarded the Life Membership in both the Professional Photographers of America, and the Kansas Professional Photographers Assn. He was Past President of the KPPA, and held the esteemed degrees of Master of Photography and Photographic Craftsman from the PPA.

As for his roots, he would always offer soldiers a free portrait sitting, as the kind Frenchmen once did for him.

WHAT MILITARY ASSOCIATIONS ARE YOU A MEMBER OF, IF ANY? WHAT SPECIFIC BENEFITS DO YOU DERIVE FROM YOUR MEMBERSHIPS?

He was a Charter Member of the National WWII Memorial, and gave quite generously to it. We visited the Memorial in Washington D.C. a few years back. He was moved by the tribute as are most World War II veterans.

My dad was a member of the VFW ever since  the end of WWII and until his death in April of 2014. the end of WWII and until his death in April of 2014.

He was not real active in the organization, but took great pride in his membership. In the small town where he lives, the VFW primarily was social.

My dad did not drink, or hang out at the "V", but he did get involved in their community projects from time to time. At his Bronze Star Ceremony in 2011, the local VFW sent a delegation with color guard.

He was also a charter member of The Red Dragons Assn., an organization of current Second Chemical Bn members and veterans, as well as WWII and Korean Era Second Chemical Mortar Bn vets. Through this organization he spoke to current soldiers of 2nd Chemical, recalling his experiences, and listening to theirs.

In this way he gave back, by way of experiences and thoughts, as he spoke to students and soldiers, alike. He felt it was an obligation to those who had died, to preserve their memory, by telling younger generations, of the supreme sacrifice of so many, and what that time in US History really stood for.

The photo is my dad at Ft Hood, talking to current soldiers of the Second Chemical Bn. about the early days of the unit, and giving them a glimpse of what the military was like, during WWII. Conversely, the soldiers showed him a good time and let him play around in the Stryker Simulator.

IN WHAT WAYS HAS SERVING IN THE MILITARY INFLUENCED THE WAY YOU HAVE APPROACHED YOUR LIFE AND YOUR CAREER?

He always had a sense of discipline. Growing up on a farm with a big family in Kansas during The Great Depression certainly played a fair role in this. But it was the self- discipline, while under duress, and in the everyday activities of army life,  that he attributed to his success as a businessman. that he attributed to his success as a businessman.

He had a sense of integrity that he gleaned from his wartime experience, one that always put others first. He ran his business and lived his everyday life with the same values that were instilled into him, so many years ago.

He never boasted. He was a selfless individual, and loved by all who knew him. He is a testament to what soldiers of his generation strived for; quiet unsung heroes that would never in a million years call themselves a hero. My dad once said something, long ago, that was very similar to a quote I read from Major Winters "Beyond Band of Brothers: The War Memoirs of Major Dick Winters." I cannot remember my dad's words exactly, but when I read Winters' memoirs, I recall it was something very much like what he had said. "I was not a hero, but I served in a company of heroes."

That was the same humility of my father. War changes people. For some, it becomes a cross to bear. For others, like my father, those experiences are like a knot in a tree. You learn from it, and grow stronger.

BASED ON YOUR OWN EXPERIENCES, WHAT ADVICE WOULD YOU GIVE TO THOSE WHO HAVE RECENTLY JOINED THE ARMY?

The advice I heard him give, on occasion, was to steer clear of temptations and to follow the rules. "Military discipline and the institution of rules and codes of conduct are an evolving process, built upon years of experience," he said.

These will not only potentially save your life, but  are also a code to live by. You will succeed in the military if you do your job. You will go far if you strive to be the best you can be. My dad told me that lives depended upon his decisions during the war. Sometimes lives were lost, but he always did his best to make the right decisions, based upon solid knowledge and experience. are also a code to live by. You will succeed in the military if you do your job. You will go far if you strive to be the best you can be. My dad told me that lives depended upon his decisions during the war. Sometimes lives were lost, but he always did his best to make the right decisions, based upon solid knowledge and experience.

No one can fault you if you do your best, and the experience you gain will last you a lifetime. Not one day went by in my dad's life, that he did not reflect upon his Army experience, for that I am certain. How you look back upon it, will depend upon how you lived it.

My dad told me, to take advantage of every educational opportunity the military provided, and to show enthusiasm.

IN WHAT WAYS HAS TOGETHERWESERVED.COM HELPED YOU REMEMBER YOUR MILITARY SERVICE AND THE FRIENDS YOU SERVED WITH.

I cannot speak for my father on this, but for myself it has given me the desire to rekindle old friendships. I cannot speak for my father on this, but for myself it has given me the desire to rekindle old friendships.

Where my father is concerned, it has given me the ambition to finish a very complete military history on his experiences and reflections, and to compile the text and photos into a book form, for his descendants and friends and those who may have an interest in his very small part in a much larger and noble cause.

This site gives me the chance to honor those of my family who have served. And for that I thank the administrators.

|

Read Other Interviews in the TWS Voices Archive | Share this Voices Edition on:

|

|

TWS VOICES

Voices are the personal stories of men and women who served in the US Military and convey how serving their Country has made a positive impact on their lives. If you would like to participate in a future edition of Voices, or know someone who might be interested, please contact TWS Voices HERE.

This edition of Army Voices was supported by:

Army.Togetherweserved.com

For current and former serving Members of the US Army, US Army Reserve and US Army National Guard, TogetherWeServed.com is a unique, feature rich resource helping Soldiers re-connect with lost Brothers, share memories and tell their Army story.

To join Army.Togetherweserved.com, please click HERE.

| |