It was a cloudy, breezy morning on Tuesday, June 6, 1944 as the largest seaborne invasion in history began when British, Canadian and American troops set off across the unpredictable, dangerous English Channel from Portsmouth, England. Their destination: the beaches at Normandy, France.

As the 5000-ship convoy carrying over 150,000 men and nearly 30,000 vehicles made its way across the choppy channel, thousands of paratroopers and glider troops were already on the ground behind enemy lines, securing bridges and exit roads. More than 300 planes dropped 13,000 bombs over coastal Normandy immediately in advance of the invasion. Naval guns fired volley after volley on and behind the beaches.

Allied infantry and armored divisions began landing on the coast of France starting at 06:30. They landed under heavy, deadly fire from gun emplacements overlooking the beaches, and the shore was mined and covered with wooden stakes, metal tripods, and barbed wire, making the work of the beach clearing teams difficult and dangerous. Strong winds also blew the landing craft east of their intended positions,  particularly at Utah and Omaha were American troops were to secure. The British and Canadians overcame light opposition to capture beaches codenamed Gold, Juno and Sword, as did the Americans at Utah Beach. Casualties were heaviest at Omaha where American troops faced heavy resistance from heavily entrenched enemy atop the high white cliffs.

particularly at Utah and Omaha were American troops were to secure. The British and Canadians overcame light opposition to capture beaches codenamed Gold, Juno and Sword, as did the Americans at Utah Beach. Casualties were heaviest at Omaha where American troops faced heavy resistance from heavily entrenched enemy atop the high white cliffs.

Considering the massive size and scope of the attack it went pretty much as planned. But the terrible conditions and enormous challenges of the attack also brought about terrible, fatal, human errors. Hampered by overcast skies, a great number of troop  transports overshot their drop zones by miles. Aircraft missed dropping airborne troops in designated drop zones, resulting in scattered units unable to hookup for hours, sometimes days. Troop carrying gliders crashed into obstacles set up by the Germans killing hundreds of paratroopers. Sixty percent of all equipment parachuted in was lost. There was staggering loss of life and limb, yet, in spite of incalculable risks, the invasion succeeded it purpose. Within days more than 100,000 soldiers had begun the slow, hard trek across Europe. By late August 1944, all of northern France had been liberated, and by the following spring the Allies had defeated the Germans. The Normandy landings was the beginning of the end of war in Europe.

transports overshot their drop zones by miles. Aircraft missed dropping airborne troops in designated drop zones, resulting in scattered units unable to hookup for hours, sometimes days. Troop carrying gliders crashed into obstacles set up by the Germans killing hundreds of paratroopers. Sixty percent of all equipment parachuted in was lost. There was staggering loss of life and limb, yet, in spite of incalculable risks, the invasion succeeded it purpose. Within days more than 100,000 soldiers had begun the slow, hard trek across Europe. By late August 1944, all of northern France had been liberated, and by the following spring the Allies had defeated the Germans. The Normandy landings was the beginning of the end of war in Europe.

Among the American solider to hit the beaches of Normandy were dozens of young men from Bedford, a small southern town in Virginia's Blue Ridge Mountains with a population of just a little over 3,000. There were thirty-five soldiers of them, all growing up together and as America went to war, so did they. All were in the same  Army National Guard Company and in the first wave on Omaha Beach.

Army National Guard Company and in the first wave on Omaha Beach.

Of the nearly 4,500 allied soldiers who lost their lives in the bloody battle, nineteen were from Bedford. Later in the campaign, four more boys from this small Virginia town died of gunshot wounds. Proportionally this community suffered the nation's severest D-Day losses. That distinction and the fact Bedford was representative of all communities, large and small, whose citizen-soldiers served on D-Day, Congress approved the establishment of the National D-Day Memorial there.

This year, the memorial is dedicating a new sculpture to honor the "Bedford Boys" and to recognize a town that, like so many others in our nation, lost their sons and brothers on one day.

On hand was CBS News reporter Jan Crawford who interviewed a number of those who grew up with the 35 Bedford boys. Among them was Lucille Boggess who was 14- years old when her two brothers, Bedford and Raymond Hoback, left home.

"My parents and most all of us went to see them off," Boggess said. "We were just kind of saying goodbye but, you know, 'We'll see you soon.' And it wasn't like they  weren't coming back." But they didn't. Both brothers are buried in the Normandy American Cemetery on a bluff above the sandy beach were they died.

weren't coming back." But they didn't. Both brothers are buried in the Normandy American Cemetery on a bluff above the sandy beach were they died.

"We were getting ready to go to church on Sunday, and the sheriff brought the first telegram. The second telegram was delivered by a cab driver," Boggess said. "Several years after that, my mother had a stroke. And I can remember that we'd be sitting around in the living room at night, and she'd be sitting on the sofa and she'd say, 'Where are my boys?' I want to cry telling you that," Boggess said.

Those in the same rifle company who survived and returned also suffered.

"I try not to think of it anymore," Allen Huddleston said.

Another Bedford boy who made it home was Sgt. Roy Stevens, who died in 2007. His daughter Kathy said her father and his twin brother, Ray, both landed on the beaches, but only Roy survived. He last saw his brother Ray when they set out for Normandy on different boats. Ray wanted to shake hands with him, and Roy wouldn't because he said, 'I'm going to see you when we get to Normandy,' and 'course, Ray didn't make it, he was one of the first ones out," Kathy said.

"I've often thought, 'Well, if all these men had come back, how would this community be different and what contribution would they have made?' And I just felt like it would've been a better place, and I think that we still sort of cry for them and miss  them," Boggess said.

them," Boggess said.

Understandable, the human cost of "The Longest Day" still casts a shadow over this town, seven decades later.

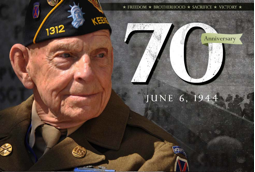

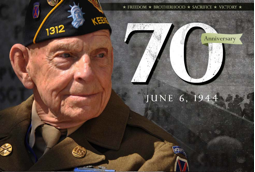

The biggest ceremony of the day took place at the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial overlooking the Normandy beach itself. Thousands of people returned to the site of that pivotal battle in this year's commemorations to mark its 70th Anniversary.

With French and American flags fluttering in a gusty breeze, President Barack Obama, together with French President Francois Hollande, addressed an audience seated against a backdrop of rows upon rows of headstones overlooking the site of the battle's most violent fighting at Omaha Beach. He described D-Day's violent scene in vivid terms, recalling that "by daybreak, blood-soaked the water" and "thousands of rounds bit into flesh and sand."

Sharing the stage with the heads of state were approximately 400 World War II veterans of that fierce battle who traveled long distances to the remote historic site.  When Obama recognized them, some removed their hats as the audience delivered a long-standing ovation. While listening to the speeches, almost all reacted with standing applause and emotion, now sitting only miles from where they fought for their lives.

When Obama recognized them, some removed their hats as the audience delivered a long-standing ovation. While listening to the speeches, almost all reacted with standing applause and emotion, now sitting only miles from where they fought for their lives.

For many veterans who survived the invasion to tell their story this could mark the last for them. With every year that passes, fewer and fewer veterans can muster the strength to return.

So much sacrifice -- a debt we can never repay or forget.

The young filly showed great promise every time she ran a race. Many believed she would be a prize winner. But she never got the chance. In June 1950, North Korean troops stormed across the border between South Korea in a surprise attack that changed life on the Korean Peninsula. It also brought the sport of horseracing to a standstill. With no races to run, owning racehorses became a financial liability for their owners. Like many others, she was abandoned at the Seoul racetrack. A young Korean stable boy named Kim Huk Moon took overfeeding, watering and grooming her.

In October 1952 some U.S. Marines from the 5th Marines' Anti-Tank Company's Recoilless Rifle Platoon discovered the young filly and decided she'd be valuable for carrying supplies into combat. The platoon leader, Lt. Eric Pederson, paid $250 of his own money to buy her. The only reason Kim sold his beloved horse was so he could buy an artificial leg for his older sister, Chung Soon, who lost her leg in a land mine accident.

Because she would be transporting the Recoilless Rifle into battle, the Marines decided she be named Reckless. During her training, she quickly became a unit mascot and allowed to roam freely through the camp. On cold nights she slept in the Marine's tents. She was known to eat anything and everything. Among her favorites were scrambled eggs and pancakes in the morning washed down with a fresh cup of coffee. She also loved sweets of all kinds: cakes, cookies, even the hard chocolate bars that came with C-rations. When she got bored she was known to eat blankets, hats, even poker chips.

But her bravery under fire and her innate intelligence in numerous battles made her a hero. Learning each supply route after only a couple of trips, she often traveled to deliver supplies to the troops on her own, without the benefit of a handler.

But her bravery under fire and her innate intelligence in numerous battles made her a hero. Learning each supply route after only a couple of trips, she often traveled to deliver supplies to the troops on her own, without the benefit of a handler.

One of Reckless' finest hours came during the Battle of Outpost Vegas in March of 1953. This particular battle, according to one writer "was to bring a cannonading and bombing seldom experienced in warfare ... twenty-eight tons of bombs and hundreds of the largest shells turned the crest of Vegas into a smoking, death-pocked rubble." Reckless was in the middle of all of it.

In a single day during the battle, she made 51 trips on her own, carrying over 9,000 pounds of ammunition and walked over 35 miles through open rice paddies ignoring  the sounds of battle as artillery exploded around her. When she returned to the ammo dump, she often carried wounded soldiers down the mountain to safety, unload them, get reloaded with ammo, and off she would go back up to the guns and the din of battle. She also provided a shield for several Marines who were trapped trying to make their way up to the front line. Wounded twice, she didn't let that stop or slow her down from carrying out her duties.

the sounds of battle as artillery exploded around her. When she returned to the ammo dump, she often carried wounded soldiers down the mountain to safety, unload them, get reloaded with ammo, and off she would go back up to the guns and the din of battle. She also provided a shield for several Marines who were trapped trying to make their way up to the front line. Wounded twice, she didn't let that stop or slow her down from carrying out her duties.

She was given the battlefield rank of corporal in 1953, and then a battlefield promotion to sergeant in 1954, several months after the war ended. She also became the first horse in the Marine Corps known to have participated in an amphibious landing.

Her military decorations include two Purple Hearts, Good Conduct Medal, Presidential Unit Citation with Star, National Defense Service Medal, Korean Service  Medal, United Nations Service Medal, Navy Unit Commendation, and Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation, all of which she wore proudly on her red and gold blanket.

Medal, United Nations Service Medal, Navy Unit Commendation, and Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation, all of which she wore proudly on her red and gold blanket.

Sgt. Reckless was a household name in the 1950s earing her media coverage that rivaled attention bestowed on other famous animals, including Lassie and Seabiscuit.

Her wartime service record, featured in The Saturday Evening Post, and LIFE magazine, recognized her as one of America's 100 all-time heroes, alongside George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

When the war ended in 1953, she was retired and brought to the United States to live out her retirement years at Camp Pendleton. Her popularity continued where she made appearances on television and participated in the United States Marine Corps birthday ball. A horse so heroic during the Korean War, she was officially promoted to staff sergeant in 1959 by Gen. Randolph McC Pate, the Commandant of the Marine Corps. Seventeen hundred Marines marched in her honor during her promotional ceremony.

Sgt. Reckless was well cared for and treated as a VIP during her time at Camp Pendleton where she produced four foals. She developed arthritis in her back as she aged and injured herself on July 13, 1968, by falling into a barbed wire fence. She died under sedation while her wounds were being treated. At the time of her death, she was estimated to be 19 or 20 years old.

Sgt. Reckless was well cared for and treated as a VIP during her time at Camp Pendleton where she produced four foals. She developed arthritis in her back as she aged and injured herself on July 13, 1968, by falling into a barbed wire fence. She died under sedation while her wounds were being treated. At the time of her death, she was estimated to be 19 or 20 years old.

Although so famous in her day, she is mostly forgotten by history. Author and screenwriter Robin Hutton is doing something about that. Upon hearing the horses' story for the first time, she got goose bumps. She is quoted as having said, "When I first heard of her story eight years ago, the first thing that came to my mind was why haven't heard of this horse before? She should have had at least three movies done on her. But when I Googled her name, there was nothing on her. It was a travesty and I started writing a screenplay and later the book 'Sgt. Reckless America's War Horse.'" The book is due out in August. Documentary filmmaker Victoria Racimo is marketing it to HBO.

Racimo's short documentary of Sgt. Reckless was shown at the 2014 Kentucky Derby and together with Hutton they succeeded in having a race named and run in her honor during the 8th race at Kentucky Oaks.

Robin Hutton also led the effort to see Sgt. Reckless immortalized in bronze. "I just thought she needed to have a monument so people would forever know who she was," Hutton said.

Robin Hutton also led the effort to see Sgt. Reckless immortalized in bronze. "I just thought she needed to have a monument so people would forever know who she was," Hutton said.

A statue by sculptor Jocelyn Russell of Sgt. Reckless carrying ammunition shells and other combat equipment was unveiled on Friday, July 26, 2013, in Semper Fidelis Memorial Park at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, one day before the 60th anniversary of the Korean War.

There is a lock of her tail hair in the base of the statue.

By Andrew Lubin

It's called it a Dignified Transfer, which is Pentagon-ese for bringing home the body of one of our young men. On my recent embed in Kandahar, Afghanistan, I flew there from Camp Bastion on a cargo flight. The plane was virtually empty: four passengers and me, the small Air Force crew and, covered by an American flag, the remains of a serviceman killed that morning by an IED in Helmand Province. The military's goal is to bring our dead back home within 48 hours, and this was the first leg of such a journey.

While I know his identity and how he died, I didn't know him personally. After 12 embeds, however, I've met hundreds of young men like him; under 25, proud of his unit, usually a couple of tattoos, enthusiastic, friendly, willing to share his last bottle of water with you, and eager for me to tell the American public that "we're doing some good things here."

Usually flights into Kandahar are lively as the troops and private contractors are heading home from here. People are relaxed, reading paperbacks, listening to their iPods, or trying to talk. But not today; the only sound was that of the plane's engines. Most of our group had their heads down. When I saw someone move, it was one of the Air Force crew adjusting the  flag draping the young man.

flag draping the young man.

I couldn't take my eyes off the flag. Unlike 99 percent of the media who cover the war, I'm not an impartial observer; my son is active-service with multiple deployments under his belt. I know too many Marines in this age group not to be affected by this young man's sad trip home; I imagined my son or one of his friends coming home the same way. How would I react I wondered (as do many of us parents of deployed sons) if they came and knocked on my front door?

After we landed, our plane came to a halt in a corner of the airfield, away from the daily bustle of troops, contractors and cargo pallets. The rear of the plane opened to reveal a small honor guard assembled to ready him for his final flight home. As our small group prepared to walk off the plane through the forward hatch, a Marine Chief Warrant Officer and I lagged behind to pay our respects to the young man. The Gunner removed his Kevlar and bowed his head, and I, a non-practicing Roman Catholic, offered a sign of the cross before the Air Force crew gently pushed us to depart.

I wanted to stay and watch the ceremony, but with one of the crew shaking his head, I grabbed my bag and hurried to catch up to our group. Walking to the terminal all I could think about was how fiercely proud I hope his family is of him. Oh, young man, you'll be missed.

I wanted to stay and watch the ceremony, but with one of the crew shaking his head, I grabbed my bag and hurried to catch up to our group. Walking to the terminal all I could think about was how fiercely proud I hope his family is of him. Oh, young man, you'll be missed.

Andrew Lubin is a foreign policy-defense analyst and author specializing in military, foreign policy, and defense issues. From Ramadi to Fallujah to Garmsir, he's brought America the stories of our deployed men and women in Iraq, Afghanistan, Haiti, and Beirut.

As Reported by REUTERS

On Feb. 24, 1968, Don Skinner was in charge of maintaining bombing radars in Vietnam when his unit came under attack. The Air Force sergeant was critically wounded, spending three months in a Saigon hospital, before being air-lifted to the States where he says he spent nine more months at a hospital "being put back together."

Three of his comrades were killed during that assault, and overall, 19 members from Skinner's unit lost their lives during the war.

But the memories of those 19 men - and hundreds of others spanning different wars - live on, thanks to Skinner's efforts. Today, the 83-year-old sits in front of a computer at his Aiken, S.C. home working on remembrance profiles for fallen soldiers. The retired veteran is one of more than 200 volunteers who work around the clock building the Roll of Honor on TogetherWeServed.com, an online war memorial that claims 1.5 million members and has more than 100,000 pages honoring fallen service members.

For Skinner, who has personally completed more than 850 profiles, it's about putting stories to names, bringing those killed in action from "obscurity back to reality."

"They are now honored and remembered," Skinner said. "These people are no longer forgotten or lost in the mist of history."

"They are now honored and remembered," Skinner said. "These people are no longer forgotten or lost in the mist of history."

Erasing that mist is not always an easy task. For example, there's a dearth of information on many Korean War and World War II veterans, whose numbers are dwindling. Volunteers rely heavily on battle history archives, gravesite information and public records to glean information, but they often must track down surviving family members to fill in the holes.

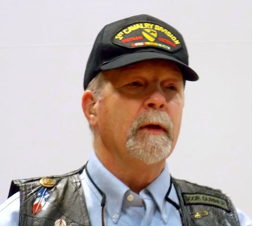

One of those working to fill the gaps is Carl "Krusty" Elliott. During the Vietnam War, the Army staff sergeant worked at Walter Reed hospital, where he says the wounded soldiers "left a lasting impression" on him.

The 67-year-old Elliott, who has built more than 2,000 online memorials from his Rochester, New Hampshire home, says it was especially gratifying to complete the profile of 1st Lt. Verne Kelley, a 10-year Army veteran who was killed in action in Vietnam in 1969. Kelley grew up not far from Elliott's hometown and was friends with his older brothers.

The 67-year-old Elliott, who has built more than 2,000 online memorials from his Rochester, New Hampshire home, says it was especially gratifying to complete the profile of 1st Lt. Verne Kelley, a 10-year Army veteran who was killed in action in Vietnam in 1969. Kelley grew up not far from Elliott's hometown and was friends with his older brothers.

Diane Short, a Navy veteran who oversees operations and management of the website's memorial teams, says the site hopes to complete unfinished profiles by year's end but the task is daunting. The online memorial includes almost 48,000 fallen soldiers in the Army alone and TWS has completed about 65 percent of those remembrance profiles.

The veterans who add photos, medals and remembrances to the online memorials are giving an emotional lift to families of the fallen. Just ask Debra Booth, whose 23-year-old son Marine Lt. Joshua Booth was killed in Iraq in 2006 -- just five weeks after deployment. She hadn't seen any photos of her son in Iraq until she stumbled upon three images of Josh posted on Together We Served. "What an amazing surprise that day," said Booth, who added that she has since corresponded with Josh's captain, hopes to connect with more men who served with her son.

Josh left behind a daughter Grace, who is now 8 years old. Debra Booth says Grace recently asked Santa Claus to bring her pictures of her daddy. Thanks to the images posted to Together We Served that wish was granted. "It's an amazing gift," Booth said of the online memorial.

Josh left behind a daughter Grace, who is now 8 years old. Debra Booth says Grace recently asked Santa Claus to bring her pictures of her daddy. Thanks to the images posted to Together We Served that wish was granted. "It's an amazing gift," Booth said of the online memorial.

Building the remembrance profiles is a healing process for the volunteer veterans, according to Short.

"A lot of these guys are dealing with PTSD," Short said. "It is their way of getting into their head and dealing with their memories and putting pen to paper honoring those who they lost."

Denny Eister, a 69-year old Vietnam War veteran who lives in Destin, Florida, says he suffers from PTSD and repressed his war memories for nearly four decades. One day, his kids uncovered some medals in his desk drawer and he says it triggered a renewed interest to track down his fellow soldiers. Eister, who works part time as an insurance agent, has since built nearly 1,000 remembrance profiles.

"You develop a bond that's hard to explain to someone who hasn't experienced combat in military," Eister said.  "It's an honor to do it for the guys who didn't come home." Eister said through his work he was able to track down his company commander at the time, Walter Dillard, who retired as a colonel and now lives in Virginia. "We still communicate to this day," he said.

"It's an honor to do it for the guys who didn't come home." Eister said through his work he was able to track down his company commander at the time, Walter Dillard, who retired as a colonel and now lives in Virginia. "We still communicate to this day," he said.

Indeed, Together We Served has become a coveted social network for veterans. Barbara (Bobbe) Stuvengen served in the Navy in World War II as a WAVE (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). A few years ago, when the 89-year-old Wisconsin resident lost her husband (also a sailor) to Alzheimer's disease, she credits the website for "preserving my sanity during some very stressful times."

"It's just kind of a way to keep in touch with the outside world," said Stuvengen, who communicates regularly with other members. "It means a lot to me to have TWS to go into. ... I begin to feel like they're my family."

As for Skinner, 65 years after enlisting in the Air Force, he is still devoting his time to serving his country. The author of several military books, he continues digging into databases, scouring archives and phoning families to piece together the lives of fallen service members. More than four decades after making it through that deadly assault in Vietnam, Skinner is battling cancer - but his doctors have declared him healthy and he remains focused on his work.

As for Skinner, 65 years after enlisting in the Air Force, he is still devoting his time to serving his country. The author of several military books, he continues digging into databases, scouring archives and phoning families to piece together the lives of fallen service members. More than four decades after making it through that deadly assault in Vietnam, Skinner is battling cancer - but his doctors have declared him healthy and he remains focused on his work.

"I guess I'm a survivor in more ways than one," he says.

The First Battle of the Somme is famous chiefly on account of the loss of 58,000 British troops (one third of them killed) on the first day of the battle, July 1, 1916, which to this day remains a one-day record

The attack was preceded by an eight-day preliminary bombardment of the German lines, with expectations that the ferocity of the bombardment would entirely destroy all forward German defenses, enabling the attacking British troops to practically walk across No Man's Land and take possession of the German front lines from the battered and dazed German troops.

However the advance artillery bombardment failed to destroy either the German front line barbed wire or the heavily-built concrete bunkers the Germans had carefully and robustly constructed. Much of the munitions used by the British proved to be 'duds' - badly constructed and ineffective.

The attack was by no means a surprise to the German forces. The chief effect of the eight-day preliminary bombardment served merely to alert the German army to imminent attack.

The first attacking wave of the offensive on July 1, 1916 went over the top from Gommecourt to the French left flank just south of Montauban. Many troops were killed or wounded the moment they stepped out of the front lines into No Man's Land. Many men walked slowly towards the German lines, laden down with supplies, expecting little or no opposition. They made for incredulously easy targets for the German machine-gunners.

The first attacking wave of the offensive on July 1, 1916 went over the top from Gommecourt to the French left flank just south of Montauban. Many troops were killed or wounded the moment they stepped out of the front lines into No Man's Land. Many men walked slowly towards the German lines, laden down with supplies, expecting little or no opposition. They made for incredulously easy targets for the German machine-gunners.

The British troops were for the most part forced back into their trenches by the effectiveness of the German machine gun response.

Despite heavy losses during the first day - 58,000 British troops alone – the offensive  persisted in the following days. Advances were made, but these were limited and often ultimately repulsed.

persisted in the following days. Advances were made, but these were limited and often ultimately repulsed.

Despite the slow but progressive British advance, poor weather - snow - brought a halt to the Somme offensive on November 18. During the attack the British and French had gained only seven and a half miles of ground, the taking of which resulted in 420,000 estimated British casualties, including many of the volunteer 'pal's' battalions, plus a further 200,000 French casualties. German casualties were estimated to run at around 500,000.

By William "Bill" Peterson

At the age of 19, William E. Peterson embarked upon a life mission which many would gladly have missed. He went to war in Vietnam! In this 302 page book he brings to life his journey from his decision to enlist in the Army, through twelve months  of helicopter combat, to his return home. It takes the reader on a wild ride with a helicopter crew chief and door gunner with the First Air Cavalry, C/227th Assault Helicopter Battalion.

of helicopter combat, to his return home. It takes the reader on a wild ride with a helicopter crew chief and door gunner with the First Air Cavalry, C/227th Assault Helicopter Battalion.

The typical memoir written by a Vietnam veteran begins with a short accounting of his youth and ends with his homecoming. Sandwich between is a detailed rendering of the serious, heartbreaking nature of war: fear, tragedy, loss, sorrow, growth, and relief interlaced with nature's emotional shutoff valve, humor.

While Peterson's Mission of Fire and Percy does much of the same things, his writing has much greater clarity since it is drawn from scores of letters he send home to his family, friends and girlfriend Cindi. He adds anecdotal recollections to what he left out in the letters that describe his daily routine and often, expresses how he feels about the fighting, calling it an "ugly, nonsensical war." But he always reminds us how a strong faith in God got him through many of the struggles of combat and the terrible loss of friends.

Reading the book takes the reader into the thick of battle as experienced by Peterson and his comrades. One feels the rush of adrenaline as they ride into battle with their machine guns blazing, enemy bullets ripping through the skin of the helicopters, the  smell of cordite from all the gunfire, the fear of the troops they shuttle into a hot LZ and the horror of taking out dead Americans or unable to stop the bleeding of a badly wounded soldier who dies before reaching a hospital. These were the missions of fire and mercy so vividly written by Peterson allowing the reader to realize his true purpose was always about protecting his comrades on the ground.

smell of cordite from all the gunfire, the fear of the troops they shuttle into a hot LZ and the horror of taking out dead Americans or unable to stop the bleeding of a badly wounded soldier who dies before reaching a hospital. These were the missions of fire and mercy so vividly written by Peterson allowing the reader to realize his true purpose was always about protecting his comrades on the ground.

But this compelling and riveting book doesn't end in his homecoming from Vietnam.

In the next to last chapter, Peterson writes about a Vietnam waitress, Ms. Amy Trinh, he met in the Marriot Hotel in 1999. Following her shift, she sat with Peterson and his co-pilot, Steve Lay and when asked what it was like when the Communist took over she hesitated, then spoke quietly about how her father was killed by the Communist for fighting in the war and her brother Robert arrested for war crimes and put in prison. Worried about their own safety, Amy and her mother fled the country.

When they departed, Peterson writes, "...we hugged and cried healing tears together. I felt I had finally 'come home'"

In Peterson's down to earth writing style the book is an easy read and once you start reading this classic about the helicopter war during the Vietnam War you will not want to put it down until you reach the end.

Reviews

The door gunner has no equal when it comes to gallantry and just plain grit. Every grunt who it has flown into a hot LZ, has watched the door gunner at work, laying down blazing fire on the enemy, keeping his head down, while offloading and prepping for the next assault. After the war, the UH-1 Helicopter and actions of the door gunner were just fleeting memories. The author has brought them back to life.

-J.N. McFadden, CWO Aviation (Retired)

This is a well-written story about a crew member on a Huey helicopter, standing in the doorway, shooting it out with a skillful and determined enemy hidden in the jungles of Vietnam.

-Gunnar F. Wilster, Capt., USN (Retired)

Get ready to climb into a Huey and ride the skies with the Ghost Riders, a place where very few have gone. Missions of Fire and Mercy is more than a war story; it is the true experience of a warrior recounted in a tasteful manner that everyone can appreciate. You won't want to miss this tour of duty.

-SP5 Eddie G. Hoklotubbe, Ghost Riders Door gunner, '67-'68

About the Author

William "Bill" Peterson was raised in Carney, a small rural town in Upper Michigan,  where he learned how to hunt and was taught by his father to make every shot count. Little did he know at the time that this training would be extremely useful within a few years!

where he learned how to hunt and was taught by his father to make every shot count. Little did he know at the time that this training would be extremely useful within a few years!

He was a flight instructor for both airplanes and helicopters, and worked as a corporate pilot for 18 years. Log home builder, taxidermist, and owner and operator of a trucking company are just a few of his former professions.

Peterson had written a couple of magazine articles prior to writing about his '67-'68 tour in Vietnam. After 15 years of passionate writing, the author released his first book: 'Missions of Fire and Mercy: Until Death Do Us Part.' In 2011, Peterson won the Silver Medal Award for memoirs from the Military Writer's Society of America Awards Program. After his well-received first book, he felt something was missing. He decided that even though he didn't know most grunts personally, it was his duty to honor them by writing 'Chopper Warriors: Kicking the Hornet's Nest.'

When he's not writing, Peterson works as a home inspector and resides in Piney Flats, Tennessee with his wonderful wife, Cindi.

He is a member of The National Purple Heart Hall of Fame.

particularly at Utah and Omaha were American troops were to secure. The British and Canadians overcame light opposition to capture beaches codenamed Gold, Juno and Sword, as did the Americans at Utah Beach. Casualties were heaviest at Omaha where American troops faced heavy resistance from heavily entrenched enemy atop the high white cliffs.

particularly at Utah and Omaha were American troops were to secure. The British and Canadians overcame light opposition to capture beaches codenamed Gold, Juno and Sword, as did the Americans at Utah Beach. Casualties were heaviest at Omaha where American troops faced heavy resistance from heavily entrenched enemy atop the high white cliffs. transports overshot their drop zones by miles. Aircraft missed dropping airborne troops in designated drop zones, resulting in scattered units unable to hookup for hours, sometimes days. Troop carrying gliders crashed into obstacles set up by the Germans killing hundreds of paratroopers. Sixty percent of all equipment parachuted in was lost. There was staggering loss of life and limb, yet, in spite of incalculable risks, the invasion succeeded it purpose. Within days more than 100,000 soldiers had begun the slow, hard trek across Europe. By late August 1944, all of northern France had been liberated, and by the following spring the Allies had defeated the Germans. The Normandy landings was the beginning of the end of war in Europe.

transports overshot their drop zones by miles. Aircraft missed dropping airborne troops in designated drop zones, resulting in scattered units unable to hookup for hours, sometimes days. Troop carrying gliders crashed into obstacles set up by the Germans killing hundreds of paratroopers. Sixty percent of all equipment parachuted in was lost. There was staggering loss of life and limb, yet, in spite of incalculable risks, the invasion succeeded it purpose. Within days more than 100,000 soldiers had begun the slow, hard trek across Europe. By late August 1944, all of northern France had been liberated, and by the following spring the Allies had defeated the Germans. The Normandy landings was the beginning of the end of war in Europe. Army National Guard Company and in the first wave on Omaha Beach.

Army National Guard Company and in the first wave on Omaha Beach. weren't coming back." But they didn't. Both brothers are buried in the Normandy American Cemetery on a bluff above the sandy beach were they died.

weren't coming back." But they didn't. Both brothers are buried in the Normandy American Cemetery on a bluff above the sandy beach were they died. them," Boggess said.

them," Boggess said. When Obama recognized them, some removed their hats as the audience delivered a long-standing ovation. While listening to the speeches, almost all reacted with standing applause and emotion, now sitting only miles from where they fought for their lives.

When Obama recognized them, some removed their hats as the audience delivered a long-standing ovation. While listening to the speeches, almost all reacted with standing applause and emotion, now sitting only miles from where they fought for their lives.

But her bravery under fire and her innate intelligence in numerous battles made her a hero. Learning each supply route after only a couple of trips, she often traveled to deliver supplies to the troops on her own, without the benefit of a handler.

But her bravery under fire and her innate intelligence in numerous battles made her a hero. Learning each supply route after only a couple of trips, she often traveled to deliver supplies to the troops on her own, without the benefit of a handler. the sounds of battle as artillery exploded around her. When she returned to the ammo dump, she often carried wounded soldiers down the mountain to safety, unload them, get reloaded with ammo, and off she would go back up to the guns and the din of battle. She also provided a shield for several Marines who were trapped trying to make their way up to the front line. Wounded twice, she didn't let that stop or slow her down from carrying out her duties.

the sounds of battle as artillery exploded around her. When she returned to the ammo dump, she often carried wounded soldiers down the mountain to safety, unload them, get reloaded with ammo, and off she would go back up to the guns and the din of battle. She also provided a shield for several Marines who were trapped trying to make their way up to the front line. Wounded twice, she didn't let that stop or slow her down from carrying out her duties. Medal, United Nations Service Medal, Navy Unit Commendation, and Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation, all of which she wore proudly on her red and gold blanket.

Medal, United Nations Service Medal, Navy Unit Commendation, and Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation, all of which she wore proudly on her red and gold blanket. Sgt. Reckless was well cared for and treated as a VIP during her time at Camp Pendleton where she produced four foals. She developed arthritis in her back as she aged and injured herself on July 13, 1968, by falling into a barbed wire fence. She died under sedation while her wounds were being treated. At the time of her death, she was estimated to be 19 or 20 years old.

Sgt. Reckless was well cared for and treated as a VIP during her time at Camp Pendleton where she produced four foals. She developed arthritis in her back as she aged and injured herself on July 13, 1968, by falling into a barbed wire fence. She died under sedation while her wounds were being treated. At the time of her death, she was estimated to be 19 or 20 years old. Robin Hutton also led the effort to see Sgt. Reckless immortalized in bronze. "I just thought she needed to have a monument so people would forever know who she was," Hutton said.

Robin Hutton also led the effort to see Sgt. Reckless immortalized in bronze. "I just thought she needed to have a monument so people would forever know who she was," Hutton said.

flag draping the young man.

flag draping the young man. I wanted to stay and watch the ceremony, but with one of the crew shaking his head, I grabbed my bag and hurried to catch up to our group. Walking to the terminal all I could think about was how fiercely proud I hope his family is of him. Oh, young man, you'll be missed.

I wanted to stay and watch the ceremony, but with one of the crew shaking his head, I grabbed my bag and hurried to catch up to our group. Walking to the terminal all I could think about was how fiercely proud I hope his family is of him. Oh, young man, you'll be missed.

"They are now honored and remembered," Skinner said. "These people are no longer forgotten or lost in the mist of history."

"They are now honored and remembered," Skinner said. "These people are no longer forgotten or lost in the mist of history." The 67-year-old Elliott, who has built more than 2,000 online memorials from his Rochester, New Hampshire home, says it was especially gratifying to complete the profile of 1st Lt. Verne Kelley, a 10-year Army veteran who was killed in action in Vietnam in 1969. Kelley grew up not far from Elliott's hometown and was friends with his older brothers.

The 67-year-old Elliott, who has built more than 2,000 online memorials from his Rochester, New Hampshire home, says it was especially gratifying to complete the profile of 1st Lt. Verne Kelley, a 10-year Army veteran who was killed in action in Vietnam in 1969. Kelley grew up not far from Elliott's hometown and was friends with his older brothers. Josh left behind a daughter Grace, who is now 8 years old. Debra Booth says Grace recently asked Santa Claus to bring her pictures of her daddy. Thanks to the images posted to Together We Served that wish was granted. "It's an amazing gift," Booth said of the online memorial.

Josh left behind a daughter Grace, who is now 8 years old. Debra Booth says Grace recently asked Santa Claus to bring her pictures of her daddy. Thanks to the images posted to Together We Served that wish was granted. "It's an amazing gift," Booth said of the online memorial. "It's an honor to do it for the guys who didn't come home." Eister said through his work he was able to track down his company commander at the time, Walter Dillard, who retired as a colonel and now lives in Virginia. "We still communicate to this day," he said.

"It's an honor to do it for the guys who didn't come home." Eister said through his work he was able to track down his company commander at the time, Walter Dillard, who retired as a colonel and now lives in Virginia. "We still communicate to this day," he said. As for Skinner, 65 years after enlisting in the Air Force, he is still devoting his time to serving his country. The author of several military books, he continues digging into databases, scouring archives and phoning families to piece together the lives of fallen service members. More than four decades after making it through that deadly assault in Vietnam, Skinner is battling cancer - but his doctors have declared him healthy and he remains focused on his work.

As for Skinner, 65 years after enlisting in the Air Force, he is still devoting his time to serving his country. The author of several military books, he continues digging into databases, scouring archives and phoning families to piece together the lives of fallen service members. More than four decades after making it through that deadly assault in Vietnam, Skinner is battling cancer - but his doctors have declared him healthy and he remains focused on his work.

The first attacking wave of the offensive on July 1, 1916 went over the top from Gommecourt to the French left flank just south of Montauban. Many troops were killed or wounded the moment they stepped out of the front lines into No Man's Land. Many men walked slowly towards the German lines, laden down with supplies, expecting little or no opposition. They made for incredulously easy targets for the German machine-gunners.

The first attacking wave of the offensive on July 1, 1916 went over the top from Gommecourt to the French left flank just south of Montauban. Many troops were killed or wounded the moment they stepped out of the front lines into No Man's Land. Many men walked slowly towards the German lines, laden down with supplies, expecting little or no opposition. They made for incredulously easy targets for the German machine-gunners. persisted in the following days. Advances were made, but these were limited and often ultimately repulsed.

persisted in the following days. Advances were made, but these were limited and often ultimately repulsed.

of helicopter combat, to his return home. It takes the reader on a wild ride with a helicopter crew chief and door gunner with the First Air Cavalry, C/227th Assault Helicopter Battalion.

of helicopter combat, to his return home. It takes the reader on a wild ride with a helicopter crew chief and door gunner with the First Air Cavalry, C/227th Assault Helicopter Battalion. smell of cordite from all the gunfire, the fear of the troops they shuttle into a hot LZ and the horror of taking out dead Americans or unable to stop the bleeding of a badly wounded soldier who dies before reaching a hospital. These were the missions of fire and mercy so vividly written by Peterson allowing the reader to realize his true purpose was always about protecting his comrades on the ground.

smell of cordite from all the gunfire, the fear of the troops they shuttle into a hot LZ and the horror of taking out dead Americans or unable to stop the bleeding of a badly wounded soldier who dies before reaching a hospital. These were the missions of fire and mercy so vividly written by Peterson allowing the reader to realize his true purpose was always about protecting his comrades on the ground. where he learned how to hunt and was taught by his father to make every shot count. Little did he know at the time that this training would be extremely useful within a few years!

where he learned how to hunt and was taught by his father to make every shot count. Little did he know at the time that this training would be extremely useful within a few years!