| |

|

An up close and personal interview with U.S. Army Veteran and Togetherweserved.com Member:

SGT Robert D Pryor U.S. Army (1967-1969)

WHAT INFLUENCED YOUR DECISION TO JOIN THE MILITARY?

Joining the military is obviously a life altering decision. Many factors came into play. The single biggest factor in my case was that my father did not serve and discouraged his children from serving. Out of his ten children, one daughter, and all five of his sons wo re our country's uniform. re our country's uniform.

My defiance only played a small part in my decision. A sense of patriotism and civic responsibility affected my decision as well. However, the biggest single factor was my having been born in the years following World War II.

As a boy growing up in the 1950's, all of my male friends had fathers who single handedly won WWII and Korea. All too often our childhood games turned to playing war. My friends all had their tales of daring do; based on their fathers' experiences. That was a very painful childhood memory for me. So painful that I swore that if there was a war going on when I grew up, I was going to be there. I would have rather died in a far away land than have a son face his friends whose fathers may have served -- while his had not.

Of course, the draft played a part in my decision too. Upon graduation from high school, I immediately enlisted. It was my belief at the time that those who got drafted got shafted. I was small, weak and lacked courage. By enlisting, rather than being drafted, I could at least choose a career path that did not put me in harm's way.

Photo from left is of my Aunt Marjorie, Grandmother, Uncle Lester (Army WWII), Mom and my Dad holding me. I was seven months old at the time. Other children pictured, from left, are my brother Jim (Army, 18 months in Vietnam, Bronze Star w/"V"), Sisters Cathy, Margie, Judy (Marines) and brother Bill (Army, Peacetime). Not pictured my older brother Glyn (WWII) and older sister Ardath. Not born yet were my brother Champ (Army, VN Era, served in Germany) and sister Tina.

WHAT WAS YOUR SERVICE CAREER PATH?

I told Staff Sgt. Wogan Lovell Blanton, my friendly Army recruiter, that I wanted to be a surveyor. I figured that I would be out surveying for school yards and roads. What danger could there be in that? Staff Sgt. Blanton signed me up for MOS 82C. Guaranteed! He swore I would be a surveyor. He kind of glossed over the Artillery Surveyor part. Guaranteed! He swore I would be a surveyor. He kind of glossed over the Artillery Surveyor part.

In the late afternoon of July 3, 1967, I raised my hand to take the oath of service at the Armed Forces Induction Center in Los Angeles. I was led outside to a bus headed for Ford Ord. We arrived at about midnight, thus starting my military career on Independence Day.

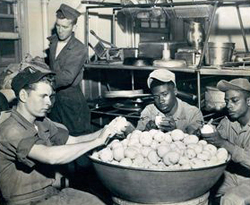

It was not until Basic Training that I learned that I would not be surveying school yards and roads. I was stuck with a bad life choice. It gave me a bad attitude and assured that my early career path included many days of KP. The mess "sergeant" was an Spec. 4, and an old guy to my way of thinking. Right off the bat I asked him how long he had been in the Army. When he told me "18 years" I laughed about him only being an E-4.

"Come with me boy, I have just the job for you," he said. Thus began my intimate acquaintance with the grease trap and my poor attitude about the Army only worsened. That attitude "impressed" the drill sergeant so my name somehow kept coming to the top of the KP duty roster. It seemed that my permanent duty station was becoming the grease trap. I even wondered if the Army had an MOS for Grease Trap Technician.

One day I was at my routine duty station when someone passed through the mess hall and asked, "Who signed up to be a paratrooper?" That certainly wasn't me. I was a little guy, a weakling and your basic all-around sissy. Then he mentioned something about having to take the Airborne PT test. I looked at the ladle that I was using to scoop out the grease trap, considered the putrid smells and said, "Me. Right here! I'm supposed to be a paratrooper."

Certainly I would fail the test, but at least I would be out of the grease trap for a bit. Besides, how could somebody be both a paratrooper and a surveyor? I tried hard on the Airborne PT test. I barely passed each segment of the test, but it kept me safely away from the grease trap for the remainder of that day. Certainly I would fail the test, but at least I would be out of the grease trap for a bit. Besides, how could somebody be both a paratrooper and a surveyor? I tried hard on the Airborne PT test. I barely passed each segment of the test, but it kept me safely away from the grease trap for the remainder of that day.

Basic Training taught me a lot about attitude and its affects on my military career. I learned how to be the grey man and never get noticed. In AIT, I managed to adjust my attitude so sufficiently that I avoided the grease trap entirely. I hoped that the Army would forget about me and the Airborne PT test. They didn't. Upon completion of the Artillery Surveying Specialist course at for Ft. Sill, Ok, I received orders for the Basic Airborne Course at Ft. Benning, Ga.

It was late fall of 1967. My jump school didn't start until January. The result was that I had a period of casual status at Fort Sill; followed by three weeks of leave time, plus travel time and/or delay en route. I did not bother to get a hair cut in all that time.

By the time I got to Ft. Benning in January of 1968, I was flat broke as I spent all my money while on leave. I still hadn't cut my hair. The company commander was not pleased. He was not about to have some "hippie" in his company. He lent me the 35 cents to go get my hair cut. There would be no "grey man" for me in Jump School.

On the Saturday between Ground Week and Tower Week I found myself at my all too frequent duty station. Someone came through the mess hall and asked, "Who signed up to take the Special Forces Battery Test?" I kept ladling. Then he mentioned that they would have to fall out and take the test. I really hated that grease trap. I threw down the ladle and said, "Me -- Right here. I'm supposed to be a Green Beret." On the Saturday between Ground Week and Tower Week I found myself at my all too frequent duty station. Someone came through the mess hall and asked, "Who signed up to take the Special Forces Battery Test?" I kept ladling. Then he mentioned that they would have to fall out and take the test. I really hated that grease trap. I threw down the ladle and said, "Me -- Right here. I'm supposed to be a Green Beret."

I would get outside, pretend to go to the testing center and then slip away to the barracks to catch up on some long-overdue rest. Outside was a bunch of mean looking soldiers yelling at us to form up. They marched us over to the testing center for a six hour test. I got no rest. But no grease trap either.

During my junior year of high school Sgt. Barry Sandler's 'Ballad of the Green Berets' was the number one song in America. All of the tough guys in my high school claimed that they would become "Green Berets." I was one of the smallest guys in my high school so everyone would have laughed at me had I made such a ridiculous suggestion.

In Tower Week I injured myself on the 34 foot tower. I still don't know what went wrong as the TAC NCO called it a successful jump, telling me to recover and make another. I pointed out that I was covered in blood. He called me a sissy, and a few other choice names, and told me to report to the aid station. I wound up in Martin Army Hospital where I lost four teeth and had a mandible reconstruction.

While recovering in the hospital, a Big Bad "Green Beret," entered the ward carrying a folder. He walked through the ward reading the names on each bed. When he got to my bunk he stopped and looked up at me with obvious disappointment. Then he asked, "Are you Private Robert Pryor?"

I tried to put on a pleasant face and answered in the affirmative. Then he goes through this long spiel asking me if I had been there for his presentation when he told my jump school class what it took to join Special Forces. Again I answered in the affirmative. He proceeded to dress me down for being a Private E-2, only 18 years old, no prior service and pointed out every other reason that I was not Special Forces material.

My heart sank. I just knew that next he was going to tell me that the Army was permanently changing my MOS to Grease Trap Technician. Instead, he said that I got a 444 on the SFBT. That meant nothing to me as I hadn't really listened to his presentation. I asked him what it meant. He told me that passing was 380 and that I got the second highest score on the day I tested. Then he asked, "Do you really want to go into Special Forces?"

I was in shock and said something stupid like, "Do you have to pull KP while in Special Forces?" Obviously puzzled by my question; he told me that I would be too busy for that.

I responded, "Where do I sign?" I have not seen the inside of a grease trap from that day to this. Oh sure, I got wounded here and there, but no more grease trap technician for me! I responded, "Where do I sign?" I have not seen the inside of a grease trap from that day to this. Oh sure, I got wounded here and there, but no more grease trap technician for me!

I called everybody I could from my childhood and bragged to them that I had been accepted into Special Forces training.

When I got to Special Forces Training Group it became immediately obvious that I didn't belong. I came close to dropping out several times. But I could not give up after bragging to friends and family about Special Forces. I could never be a store-bought warrior so I made up my mind that I was either going to make it in Special Forces or they were going to have to carry me out in a box.

I completed the Special Forces Combat Engineer course and was awarded MOS 12B2S in August of that year. Following Training Group I was assigned to the 3rd Special Forces Group. But my dream was to go to Vietnam. I still had to fulfill my childhood quest of going to war.

In order to get a coveted slot with 5th Special Forces Group in Viet Nam you had to have some rank, experience or influence. I had none of those. There was still one other path available to a young troop like me. While I was in 3rd Group I cross-trained as a Special Forces Operations and Intelligence Specialist. I also took a Vietnamese language course in the evenings. I became fully qualified in two of the five Special Forces skills and spoke a little Vietnamese. In December of 1968 my childhood dream came true. I was sent off to war.

I was assigned to Detachment A-344, 5th Special Forces Group. Our camp was at the village of Dia Diem Bunard, Don Luan District, Phouc Long Provence, III Corps Tactical Zone. That was about 65 miles north of Saigon. We didn't even have a mess hall, much less a grease trap. I was home.

Unfortunately for me I participated in what I call the 'Viet Cong Early Out Program . On June 20, 1969 I was severely wounded and my career and life path suddenly took an unexpected turn. I was sent to the 24th Medical Evacuation Hospital in Long Binh for a month or so. I don't really remember much about the place as I was asleep for most of the time. When I regained situational awareness, several days had quietly passed. . On June 20, 1969 I was severely wounded and my career and life path suddenly took an unexpected turn. I was sent to the 24th Medical Evacuation Hospital in Long Binh for a month or so. I don't really remember much about the place as I was asleep for most of the time. When I regained situational awareness, several days had quietly passed.

From Vietnam I went to the 249th General Hospital at Camp Zama, Japan. I don't remember much about that place either, other than they would put me in a wheel chair that needed two hands to operate. Only my left arm worked, so all I could do was travel in a very small circle. I must have been too shot up for the grease trap so they had to find some other way to torture me.

My next stop was at the U.S. Air Force Hospital at Travis AFB for a few days where I was treated like royalty. I knew right then and there that I should have joined the Air Force. From there it was a short chopper flight to what would become my last home in the Army -- Letterman General Hospital at the Presidio of San Francisco. I was eventually sent home on terminal leave and was placed on the Permanent Disability Retirement List effective Veterans Day, November 11, 1969. It somehow seemed appropriate for someone whose first full day in the Army was the Fourth of July.

It completed the cycle making me a full blooded nephew of my Uncle Sam. I was a military retiree who had picked up three different military Occupation Specialties, was Airborne qualified, was trained in a foreign language, served in two different Special Forces Units, spent five months in the hospital; and in just under three more months, I would finally be old enough to vote.

DID YOU PARTICIPATE IN COMBAT OPERATIONS? IF SO, COULD YOU DESCRIBE THOSE WHICH WERE SIGNIFICANT TO YOU?

My service was on a Special Forces A-team. I was never involved in any named combat operations. In fact, I saw very little action -- well -- except for the times I got wounded. Those were a bit of a sticky wicket. My service was on a Special Forces A-team. I was never involved in any named combat operations. In fact, I saw very little action -- well -- except for the times I got wounded. Those were a bit of a sticky wicket.

The job of my A-team was to train and lead an element of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG). I loved the job and I loved the people. Our CIDG were mostly Stieng Montagnards, with an element of ethnic Cambodians and a very few ethnic Vietnamese people.

The picture is of me in front of our hooch at Bunard.

WHICH, OF THE DUTY STATIONS OR LOCATIONS YOU WERE ASSIGNED OR DEPLOYED TO, DO YOU HAVE THE FONDEST MEMORIES OF AND WHY?

My time in the grease trap in Basic Training is my fondest memory. I'm just kidding. I only had one assignment that was not for training or medical care, so obviously it was my time in Vietnam. But I am not saying that because it is some sort of only choice. It was the best job I ever had in my life. I got to serve with real giants and they treated me as their equal. They even let me play with explosives without adult supervision.

On my A-Team I learned that even the low man on the totem pole gets treated with respect as long as he can perform his job as needed and expected. We developed a camaraderie that few  will ever know. I can't say if it is something about Special Forces, something about being left out on a frontier without close support, or nearly dying together that caused such a tight bond. will ever know. I can't say if it is something about Special Forces, something about being left out on a frontier without close support, or nearly dying together that caused such a tight bond.

That bond is hard to explain but there are some examples of that closeness. The surviving team members are still in contact with one another. Decades after our time in Vietnam, our Top Sergeant and I vacationed in Costa Rica together. And when I got married many years after Vietnam, not only were my team mates there for the wedding, my commanding officer was standing at my side -- he was my best man. I just can't imagine many military units where the commanding officer serves as the best man at the wedding of his lowest ranking man.

The photo was taken at Bunard in June of 1969. Pictured are Charles C. Hinson, Intelligence; Carl C. Cramer, Communications; Daniel M. Dudley, Weapons; Robert D. Pryor, Engineer; John J. Parda, Commander; Larry L. Crile, Medic; John E. Nowlan, Team Sergeant. Not pictured is Sgt. First Class Efren "Esse" Renteria, weapons; and Staff Sgt. Charles P. Orona, medic.

FROM YOUR ENTIRE SERVICE CAREER WHAT PARTICULAR MEMORY STANDS OUT?

For me it would be riding that Hell Bound Elevator. When I got wounded the second time, I had become separated from my team mates. My radio was destroyed, the two indigenous civilians that were with me had been killed, my legs and right arm had been wounded  so many times I couldn't even move them. Then, to make matters worse, my rifle also got severely wounded and rendered inoperable -- leaving me unarmed with no way to tell anybody or ask for help. so many times I couldn't even move them. Then, to make matters worse, my rifle also got severely wounded and rendered inoperable -- leaving me unarmed with no way to tell anybody or ask for help.

Oh sure, there were a bunch of Vietnamese that knew where I was, but shall we say I wasn't on their Christmas card list. They probably thought I was dead as they finally left me alone after one of them killed my rifle.

I accepted my fate. Life sucked and it was time to die. I did not deserve Heaven. Hell could be no worse than a huge grease trap and that was where I was heading.

The three team mates that had been with me that night refused to give up on me. During a lull in the fighting, 1st Lt. John Parda, our detachment commander, sent Sgt. First Class Charles Hinson to find me. I still say as it was a dumb idea, but I would like to think that I would have never given up on one of them had the positions been reversed.

In spite of getting wounded himself, Charles found me. He was awarded the Silver Star for his actions that night, as was our radio man, Sgt. First Class Carl Cramer. John Parda was awarded the Bronze Star with "V" device but desrved so much more. It was his leadership that saved the day.

None of my three team mates were medics, but they did what they could to treat my wounds. Charles went back to join the festivities as John cut off what was left of my clothes and started plugging holes. Carl was on the radio coordinating with Hinson at the same time that he was trying to summon help.

Before slipping into a coma, the last thing I member was Carl said over the radio, "I don't want him to die here on the floor of my bunker." Carl had been pleading with a med-evac to reconsider their denial of his request to come get me. I had sprung a great many leaks so I knew that the end was near, even before the med-evac was refused. Before slipping into a coma, the last thing I member was Carl said over the radio, "I don't want him to die here on the floor of my bunker." Carl had been pleading with a med-evac to reconsider their denial of his request to come get me. I had sprung a great many leaks so I knew that the end was near, even before the med-evac was refused.

Carl still has never told me where he wanted me to die, although I have asked him many times over the past several years. He just smiles at me when I ask him. Carl has a terrible bed-side manner. That's probably why they made him a commo man and not a medic.

I received four major head wounds, two of which penetrated over half way through the brain. I lost about 20% of the brain on the right side. My mind began to play tricks on me. The world was a void as I was unable to see or move. I could only hear. I hallucinated that I was watching my team mates struggling. I felt that I was wearing a turban and asking for help in removing it. No one answered my pleas. I wondered if I was already in Hell. Take my word for it; heaven was not an option in my case. At least I was not stuck in some giant grease trap -- yet.

I heard a machine-like voice talking in a strange language. The machine's voice eventually became clearer. It was in English, but made no sense. I tried to decide if it meant that I was in Hell or just lost my mind. The voice said strange things such as, a number of feet down by a fraction. Perhaps it said, "60 feet down by two and a half." Did that mean that I was riding a Hell-bound elevator? I was bewildered.

Then the machine said so many forward. They must be keeping track of how many of us going to Hell on that trip. Then came more gibberish about how many feet down and a fraction. Perhaps I was still on the elevator to Hell.

The machine said "Picking up some dust." Oh my! I wasn't in Hell, I was crazy! I tried to make some sense out of how one might go around picking up particles of dust.

Then it went back to feet down and a fraction. I was back on that Hell-bound elevator.

The mechanical voice said, "shadow," followed by more gibberish. I was so confused.

"Drifting to the right a little." Then down again. The elevator to Hell was sure taking a funny path.

"30 seconds." I was still on the elevator and almost to Hell.

"Contact Light." Damn! Was I back at Bunard? Maybe Bunard was Hell all along and I was too dumb to know it. At least the contact was now light. It had been pretty intense for awhile.

"Shutdown" Nope, I made it to Hell.

"Engine Stop." Yep, I'm there. Where's the grease trap?

More gibberish! Nope, I'm back to being crazy.

Then there was a bunch of unintelligible things that convinced me that I made it to Hell.

"We copy you down, Eagle." Yep, I'm in Hell, but the "eagle" comment was a nice touch for a soldier who just died in the Army fighting for his country.

More about the elevator ride to Hell that made no sense whatsoever

Then the mechanical voice said, "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed."

I wasn't alone. Cheers, screams and whistles erupted. The whole world was holding its collective breath during the final descent of man's first adventure to another heavenly body.

When I slipped into a comma I knew that the Apollo 11 mission would be coming in the next month or two. It turned out to be exactly 30 days after I got wounded. I knew that the Lunar Lander was called the Eagle and I knew that their primary landing site was to be in the Sea of Tranquility. It all came together like a giant cloud lifting from my head. My mind, what was left of it, was finally starting to clear.

After I lost consciousness, a lone Huey crew decided to attempt my med-evac. But the Viet Cong controlled our chopper pad. My team mates cooked up a scheme to bring a copper down inside our camp. There was a small area between the inner wall and some indigenous housing  that was perhaps 100 feet by a little over fifty feet. The Huey would have to come in oriented on a certain azimuth, dropping in and lifting out almost vertically. To guide them in, Charles Hinson stood at the appropriate spot holding a GI flashlight with a red filter; oriented towards the aircraft. that was perhaps 100 feet by a little over fifty feet. The Huey would have to come in oriented on a certain azimuth, dropping in and lifting out almost vertically. To guide them in, Charles Hinson stood at the appropriate spot holding a GI flashlight with a red filter; oriented towards the aircraft.

He was communicating on a PRC-25 that he carried. He instructed them to put the nose of the aircraft on his flashlight. With unseen buildings, fortifications and a 60 foot antenna only a few feet away, he stood there in the darkness as the Huey attempted to come in. Twice the chopper had to abort due to small arms fire. With anything less than precision airmanship in total darkness, Charles, the crew and I would be dead. As Charles stood his ground, the nose of the chopper came to rest six inches from his flashlight. John Parda and Carl Cramer rushed up to the aircraft and passed me to the crew.

My wounds were so severe that it was assumed that I would not survive. I had sustained thirty major wounds and about 200 minor wounds. But to paraphrase Mark Twain, "The reports of my death were greatly exaggerated." Or as my old Special Forces buddy Don Valentine once put it, "Pryor really did die in Vietnam. He's just is too stupid to know it."

Pictured is my mother with me while I as in Letterman General Hospital at the Presidio of San Francisco in August of 1969.

WERE ANY OF THE MEDALS OR AWARDS YOU RECEIVED FOR VALOR? IF YES, COULD YOU DESCRIBE HOW THIS WAS EARNED?

Headquarters, U.S. Army, Vietnam, General Orders No. 3422 (September 7, 1969) states:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918 (amended by act of July 25, 1963), takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Specialist Fourth Class Robert D. Pryor, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations involving conflict with an armed hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam, while serving with Detachment A-344, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces. Specialist Four Pryor distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions while serving as an intelligence specialist at Camp Bunard. During the early hours of 20 June 1969 hostile mortars and rockets began to rain on the compound and a force of enemy sappers managed to infiltrate the perimeter defense and sever communication lines between the tactical operations center and the perimeter bunkers. Specialist Pryor left his mortar pit where he had been firing illumination rounds and immediately headed for the edge of the camp. On discovering that the trench system on the east and northeast sides of the base were occupied by the Viet Cong, he commenced relaying information that enabled the operations center to direct airstrikes on the invaders. Meanwhile, Specialist Pryor rallied an element of camp strike force personnel to recapture the enemy-held positions. Spotting a number of hostile rocket emplacements near the airstrip, he quickly informed the operations center and the rocket emplacements were destroyed. After the trenches had been secured, Specialist Pryor continued to check the perimeter defense, giving encouragement to the indigenous soldiers and reporting enemy positions to the operations center. Discovering that the southeastern section of the perimeter had been overrun by the Viet Cong, he informed his superiors of the threat and then proceeded to assist two Vietnamese troops in routing the enemy. When reinforcements arrived, they found that Specialist Pryor had stood his ground, even after his two comrades had been killed and he himself had been seriously wounded. Specialist Four Pryor's extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army. the camp. On discovering that the trench system on the east and northeast sides of the base were occupied by the Viet Cong, he commenced relaying information that enabled the operations center to direct airstrikes on the invaders. Meanwhile, Specialist Pryor rallied an element of camp strike force personnel to recapture the enemy-held positions. Spotting a number of hostile rocket emplacements near the airstrip, he quickly informed the operations center and the rocket emplacements were destroyed. After the trenches had been secured, Specialist Pryor continued to check the perimeter defense, giving encouragement to the indigenous soldiers and reporting enemy positions to the operations center. Discovering that the southeastern section of the perimeter had been overrun by the Viet Cong, he informed his superiors of the threat and then proceeded to assist two Vietnamese troops in routing the enemy. When reinforcements arrived, they found that Specialist Pryor had stood his ground, even after his two comrades had been killed and he himself had been seriously wounded. Specialist Four Pryor's extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

That's not how I remember things. There are three huge factors that come into play. Obviously the war was still in full swing so the citation could never state our vulnerabilities. With only four Special Forces soldiers in the camp that night, our position had been quite tenuous at best. The second is that I was alone for all of what I considered to have been the more difficult part of the evening. Therefore, there were no witnesses to my specific actions. And lastly, with my brains shaken, as well as stirred, there is no way I can know which of my memories are accurate. Just know that things were a bit unpleasant. I would have rather been anywhere else at the time -- well, except maybe cleaning a grease trap.

There is one part of my DSC citation that particularly bothers me. The mention of the two Vietnamese troops with me is so misleading. Both were civilians, not soldiers. One of those two was an interpreter. I took him with me when I went out to mix it up with the bad guys. With the exception of some dead lead, the first round to hit me that night passed through him first. He died very early on in the battle. The second person to die at my side was a Cambodian. He was unarmed and was heroically trying to patch up some of my leaks as I was busy prosecuting the war. He gave his life saving me. Neither individual had an opportunity to engage the enemy or defend themselves before being killed. The implication that those two were somehow soldiers, doing what soldiers are trained to do, steals their valor. It took great courage to do what they did, knowing the probable outcome.

One part of my citation was a total fabrication. It was true that the only combatants on either of the walls mentioned were Viet Cong soldiers attempting to establish ownership of our camp through the right of adverse position. But there were no members of the camp strike force to be found. One part of my citation was a total fabrication. It was true that the only combatants on either of the walls mentioned were Viet Cong soldiers attempting to establish ownership of our camp through the right of adverse position. But there were no members of the camp strike force to be found.

Other than the two people that died at my side, the only "friendly" faces I saw after leaving the inner compound were women and children huddled together as they hid in fear. I directed them to safety as best I could. They didn't all make it.

I understand the fabrication in that part of the citation. The truth would have told our enemies that they had the camp and didn't know it. The media would have made sure that our enemies were aware of our vulnerabilities. That would have encouraged the bad guys to come back to finish the job.

The picture is on our camp the morning after the attack. My rifle, my radio and I were not the only things to get severely wounded that night.

OF THE MEDALS, AWARDS AND QUALIFICATION BADGES OR DEVICES YOU RECEIVED, WHAT IS THE MOST MEANINGFUL TO YOU AND WHY?

I relish my Distinguished Service Cross. It is not that I think that I earned it in any way. Nor does it reflect directly on my skill as a soldier. What is so important to me about my DSC is that is tells me what my team mates thought of my service. It was their opinion that counted, not Big Green's.

When I learned that I had been put in for the DSC by my team mates it was one of the proudest moments of my life. I just figured that it would be downgraded to a Bronze Stare with "V" device. When they told me that I was in fact going to be receiving the DSC, it was anticlimactic to me. My team mates had made their call a couple of months earlier. The awarding of the medal just meant that Big Green agreed with my team mates.

WHICH INDIVIDUAL PERSON FROM YOUR SERVICE STANDS OUT AS THE ONE WHO HAD THE BIGGEST IMPACT ON YOU AND WHY?

It is impossible to answer this question the way it is written. No one person had what I would call the biggest impact on me. The closest I can come is to say 1st Lt. John J. Parda, Master Sgt. John E. Nowlan, Sgt. First Class Charles C.  Hinson, Sgt. First Class Carl C. Cramer, Sgt. First Class Efren "Esse" Renteria, Sgt. First Class Daniel M. Dudley, Staff Sgt. Charles P. Orona and Sgt. Larry R. Crile. We were a team. They took some child and let him earn their respect. They let me do my job and show them that I was qualified to stand shoulder to shoulder with them. They were the first persons in my life to ever take me seriously. To them, "Be all you can be" was not just some slick slogan. It was a challenge -- it was what we did. Hinson, Sgt. First Class Carl C. Cramer, Sgt. First Class Efren "Esse" Renteria, Sgt. First Class Daniel M. Dudley, Staff Sgt. Charles P. Orona and Sgt. Larry R. Crile. We were a team. They took some child and let him earn their respect. They let me do my job and show them that I was qualified to stand shoulder to shoulder with them. They were the first persons in my life to ever take me seriously. To them, "Be all you can be" was not just some slick slogan. It was a challenge -- it was what we did.

The photo is of my team mates and me taken at a team reunion at Hot Springs, Arkansas in October of 2000.

CAN YOU RECOUNT A PARTICULAR INCIDENT FROM YOUR SERVICE THAT WAS FUNNY AT THE TIME AND STILL MAKES YOU LAUGH?

In early June of 1969, I got tapped for radio relay duty up on top of Nui Ba Ra: the mountain just outside of Song Be, Vietnam.

A 1st Lt. from B-34 and I represented the SF contingent, two Military Intelligence (MI) types were there, and a few CIDG for  security. The MI guys were monitoring some type of seismic sensors that were designed to pick up movement out on Uncle Ho's international trail system so that 'smoke' could be brought in upon any unauthorized foot or vehicle traffic. The 1st Lt. and I were up there providing communications for some high speed, low drag, guys operating out there in areas that might otherwise fall outside normal communication range. security. The MI guys were monitoring some type of seismic sensors that were designed to pick up movement out on Uncle Ho's international trail system so that 'smoke' could be brought in upon any unauthorized foot or vehicle traffic. The 1st Lt. and I were up there providing communications for some high speed, low drag, guys operating out there in areas that might otherwise fall outside normal communication range.

One of the two MI guys appeared to be scared the whole time. He just knew that ten thousand NVA soldiers were going to summit the mountain at any moment and we would all be dead. To make matters worse, he was trapped up there with two "crazy Green Berets." There was no telling what those crazy types might do -- and he was right.

The MI guys had all of their equipment in a bunker made from a Conex container. I couldn't help but laugh at how frightened the one guy always was so I figured that it was time to have a little fun at his expense.

One nice sunny afternoon I walked into their bunker with a grenade, pulled the pin, dropped it on the floor between us and said, "I am tired of this war."

The other MI guy, the one not scared, picked it up, and ran outside screaming, "YOU'RE CRAZY!"

He then chucked the grenade back over the bunker and into the jungle down the west side of the mountain. The grenade exploded thunderously. The guy throwing the grenade just calmly walked back into the bunker and went back to work. Needless to say, his associate was not so calm. He was even more frightened than before. He probably never got a moment's sleep until I left a few days later.

What he did not know was that standing behind the bunker was the 1st Lt., grenade in hand, with the pin already pulled. His cue to toss his grenade was when he heard the MI guy yelling. Of course, the grenade that I dropped on the floor of the bunker had already been rendered inert by me. I reassembled the grenade before walking in and dropping it. It looked and operated like a normal hand grenade -- minus the explosion.

I often wonder if his buddy, who was in on the gag all along, ever told him the truth.

The photo is of the 1st Lt. from B-34 at Song Be that helped pull off the prank on the MI guy. Unfortunately, after all these years I no longer recall his name.

WHAT PROFESSION DID YOU FOLLOW AFTER THE SERVICE AND WHAT ARE YOU DOING NOW? IF CURRENTLY SERVING, WHAT IS YOUR CURRENT JOB?

My employment always took a back seat to my disabilities. I have been rated by the VA as 100% disabled from day one. Life was a series of small victories as, one by one, I overcame my disabilities.

The first victory was graduating from diapers to a  bed pan. Next was sneaking out of my bed in the middle of the night and using an IV stand as a walker so I could go to the bathroom without assistance. Then I cast aside the wheelchair and eventually regained the use of my right arm. It took several decades before I was able to set aside my crutches and leg braces. Perhaps the biggest victory was the day I graduated from Washington State University, in spite of my diminished mental capacity. I stood up on the main stage watching my fellow students file into the coliseum. I was not up there due to some head of the line privileges for the disabled. I was there because I earned my position. I was graduating summa cum laude and at the head of the class for my discipline. bed pan. Next was sneaking out of my bed in the middle of the night and using an IV stand as a walker so I could go to the bathroom without assistance. Then I cast aside the wheelchair and eventually regained the use of my right arm. It took several decades before I was able to set aside my crutches and leg braces. Perhaps the biggest victory was the day I graduated from Washington State University, in spite of my diminished mental capacity. I stood up on the main stage watching my fellow students file into the coliseum. I was not up there due to some head of the line privileges for the disabled. I was there because I earned my position. I was graduating summa cum laude and at the head of the class for my discipline.

My first job was as a Veterans Benefits Specialist for San Bernardino County Department of Veterans Affairs. In just under three years on the job, my medical conditions began to profoundly interfere with my employment. On doctor's orders I had to quit that job. For the next several years I meandered about in a few jobs that were unfulfilling to me. I was a bar manager, a City Planner and a City Councilman. It was during my second term as a councilman that I decided to pursue my real passion. I purchased a small farm about 125 miles away and resigned my council position.

I spent 17 years as an alfalfa farmer in Eastern Washington. I loved it! I also spent ten years as the Watermaster of the local irrigation district. In 2003, I retired and am now living happily ever after in no place but Texas.

The photograph is the home I lived in while farming and serving as Watermaster.

WHAT MILITARY ASSOCIATIONS ARE YOU A MEMBER OF, IF ANY? WHAT SPECIFIC BENEFITS DO YOU DERIVE FROM YOUR MEMBERSHIPS?

In addition to Together We Serve, I am a member of the Special Forces Association, the Legion of Valor, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, The American Legion and the Disabled American Veterans. I am a Life Member of all of those organizations.

I  gain a little from each organization. I depend on them for current information on military and veterans issues. We were service members only for a specific period of time, but we will be veterans forever. I learned early on that we can't depend on the government to keep our best interests on the front burner. I depend on the organizations to look out for my best interests and keep me informed about things that affect my life. gain a little from each organization. I depend on them for current information on military and veterans issues. We were service members only for a specific period of time, but we will be veterans forever. I learned early on that we can't depend on the government to keep our best interests on the front burner. I depend on the organizations to look out for my best interests and keep me informed about things that affect my life.

The greatest single benefit I have received from any of these organizations was when the VFW named me Young Veteran of the Year in 1981. I received a very nice expense paid trip to their National Convention in Philadelphia, where I was presented that award.

The photo is of my VFW Young Veteran of the Year award.

HOW HAS MILITARY SERVICE INFLUENCED THE WAY YOU HAVE APPROACHED YOUR LIFE AND CAREER?

Obviously becoming totally disabled due to wounds can have a very profound affect on anyone's life. For one thing, you have to try harder or surrender. But what folks may not guess is that my military service gave me a passion for helping children. I have always opened my home to children in need, regardless of any financial assistance. In fact, very few of my foster children came with any kind of stipend. Two came with child support from their father. Two were orphans and came with Social Security benefits. The rest were supported solely by me. I have always opened my home to children in need, regardless of any financial assistance. In fact, very few of my foster children came with any kind of stipend. Two came with child support from their father. Two were orphans and came with Social Security benefits. The rest were supported solely by me.

I have two biological children, one step-daughter and I was fortunate enough to be allowed to adopt five children. There were fifteen other children for which I was their foster father for varying lengths of time. That made me the father figure to 23 different children in one way or another.

So what does all this have to do with the military?

Living around the civilians in Vietnam, rather than on a well established military installation, helped me to see their plight. Governments and the media dismiss what the war was doing to them as "collateral damage." I saw it as something else altogether. It was hardest on me to see children trying to grow up in the middle of a war zone. They had nowhere to run and few opportunities to hide. A big part of our job on a Special Forces A-Team was to extend the sphere of influence of the central government. I saw it more as trying to keep them alive. The most heart-wrenching part of that was witnessing children experiencing war -- to see the look of fear on their young faces -- to watch them die.

I made it a life-long goal to do what I could to help children. It sort of made up for the children I was unable to save in Vietnam.

For 34 years I had nightmares almost nightly. The dream was always the same. I wound up on the south wall of my camp, alone, unarmed and facing a bunch of bad guys. In the end, I always awoke at the point when they were about to finish me off.

In 2003, my oldest daughter asked me to do something I swore I'd never do. She asked me to take her to where I got shot. With the word "NO" not in my daddy dictionary, I honored her request. The night before we went out to Bunard to face the monsters hiding in my closet, I couldn't sleep. In part due to fear of my recurring nightmares but also due to fear that I was going to embarrass myself in front of my daughter.

There was almost no sign of the old camp, but I could tell where everything had been. It was emotional to be standing on the exact spot where Charles Hinson had found me so many years before, but not too emotional. As I held my daughter, I looked around. Instead of death and destruction, I saw crops growing. It was beautiful. Children were playing as children do. Perhaps they were wondering why two strangers would come to some remote location.

Finally it occurred to me. My daughter would never have been born had I not got shot up and sent home early. And the children! These were the decedents of the people I helped save that night. These were children that, like my daughter, might not be been born except for my part in those unpleasant events of so long ago. Finally it occurred to me. My daughter would never have been born had I not got shot up and sent home early. And the children! These were the decedents of the people I helped save that night. These were children that, like my daughter, might not be been born except for my part in those unpleasant events of so long ago.

The monsters in my closet were vanquished. I never again had a bad dream about Vietnam. Oh sure, I still dream about Vietnam from time to time. But in my dreams, crops are growing and children are playing. I truly enjoy agriculture and children shall forever have a special place in my heart. I returned to Vietnam two more times since 2003; to just enjoy the place as a tourist.

The photo is of my daughter Tracy and me standing at approximately the same spot where Sgt. First Class Hinson found me when my participation in the Vietnam War that ended 34 years earlier.

WHAT ADVICE WOULD YOU HAVE FOR THOSE THAT ARE STILL SERVING?

For those just entering the military, I tell them to pay attention to every word in training. You never know what seemingly trivial little lesson may be the one that saves your life or the life of a buddy. In a life and death situation, you will want  every possible tool at you disposal. My being a wimpy kid made me so scared that I hung on every word while I was in training. That is one of the reasons I'm here today. every possible tool at you disposal. My being a wimpy kid made me so scared that I hung on every word while I was in training. That is one of the reasons I'm here today.

Understand that discipline and the rank structure are necessary for military operations to succeed. But also understand that you might not always be right or wrong because of your rank. It is said that "rank has its privileges." That works fine for garrison duty. In combat it will be training, skill and experience that determines who lives and who dies. Let it be you that lives.

If you're in a leadership position you must fully understand the potential of every soldier. Pre-judging anyone can get good people killed. Everybody has their potential. A good leader is one who can help their subordinates achieve that potential. Subordinates performing at their full potential make their leaders look good.

Junior service members need to recognize that their superiors probably have the training and experience. That was how they got into their leadership positions. Respect that and learn from them.

Train, train, and cross-train. Learn from one another. Seize every opportunity to expand and hone your military skills. You will never know it all so if you aren't trying to learn more, you are asking for trouble.

Oh yeah -- DUCK!

The photo is of my son, USAF Master Sgt. Robert D. Pryor, Junior, at Kandahar, Afghanistan. The tradition continues.

IN WHAT WAYS HAS TOGETHERWESERVED.COM HELPED YOU MAINTAIN A BOND WITH YOUR SERVICE AND THOSE YOU SERVED WITH?

I have met old friends here, as well as made new one. Linking up with old friends helped me bring closure to a few loose ends. The new friends have helped me expand my world of knowledge and understanding of those things that happened over four decades ago. I have met old friends here, as well as made new one. Linking up with old friends helped me bring closure to a few loose ends. The new friends have helped me expand my world of knowledge and understanding of those things that happened over four decades ago.

Together We Served has also helped me to bridge the generation gap. I have connected with soldiers from other eras.

Some of my friends here have already passed on to Fiddlers' Green. But they shall continue to live here as long as the web site stays up and running. I appreciate that.

The photo combines my team from 1969 with the same guys in 2000, just as Together We Served unites the old and young. Together, we did indeed serve.

|

|

|

Share this Voices Edition on:

|

|

TWS VOICES

TWS Voices are the personal stories of men and women who served in the US Military and convey how serving their Country has made a positive impact on their lives. If you would like to participate in a future edition of Voices, or know someone who might be interested, please contact TWS Voices HERE.

This edition of Army Voices was supported by:

Army.Togetherweserved.com

For current and former serving Members of the US Army, US Army Reserve and US Army National Guard, TogetherWeServed.com is a unique, feature rich resource helping Soldiers re-connect with lost Brothers, share memories and tell their Army story.

To join Army.Togetherweserved.com, please click HERE.

|

|